A Thesis For Sector-Focused Hedge Funds

Today: What the pandemic did to (US) retail & how it could inspire hedge funds; also Graeber, France, and more.

The Agenda 👇

My interest in capital allocation

Spotting a pattern in retail

A hedge fund inspired by Carlota Perez

Alex Danco on David Graeber

Old-fashioned decentralization sucks

France lacks a Jean Monnet

After COVID-19, no more low-wage jobs

I have this weird passion for everything related to capital allocation. It’s not my background, but I’ve been digging ever deeper into it for at least 5 years now, because I sense it’s absolutely critical for both understanding and taking action in today’s context.

I started exploring that topic as an adjunct professor at Paris Dauphine University (2015-2016). I was hired there to teach business strategy in the context of the shift to the Entrepreneurial Age. I always want to use teaching as an opportunity to learn new things, so I decided to add a corporate finance tweak to my course and to dedicate my classes to exploring the financial lessons we could draw from the evolution of strategic thinking in the Entrepreneurial Age.

A most helpful author on that journey has been Michael J. Mauboussin, who when I started was the Head of Global Financial Strategies at Credit Suisse and who is now Head of Consilient Research at Counterpoint Global (which is part of Morgan Stanley). I remember having my mind blown in 2016 by studying and annotating his seminal research paper on capital allocation in the runup to writing an essay about Michael Porter’s legacy in the Entrepreneurial Age. And indeed there’s one Mauboussin idea that I think is the most important business lesson for our time:

Fund strategies, not projects. The idea here is that capital allocation is not about assessing and approving projects, but rather assessing and approving strategies and determining the projects that support the strategies. Practitioners and academics sometimes fail to make this vital distinction. There can be value-creating projects within a failed strategy, and value-destroying projects within a solid strategy.

More recently I’ve been involved in conversations about asset allocation in our times of shifting paradigms. And then as a personal hobby I’m working (slowly but surely) on constructing an investment thesis for a (theoretical) hedge fund that would seek to make money out of the transition from the Fordist Age to the Entrepreneurial Age (a hedge fund driven by Carlota Perez’s ideas, if you will).

Indeed, when thinking as a (again, theoretical) hedge fund manager, this pandemic has been rewarding. COVID-19, as an accelerator of pre-existing trends, has provided us with clear insights as to how the paradigm shift plays out in given sectors, showing who goes up and who goes down.

Take the case of retail. Here’s a simplified list of what’s been going on in the past six months:

Amazon, as you know, has been smashing it. It’s one of the hottest tech stocks these days, and for good reason. It helps that Jeff Bezos is still the best strategist and capital allocator out there. Read my Amazon: Top of the Game.

Other tech-driven retail businesses have been doing similarly well, but they had to deal with shortages in shipping and logistics because Amazon was grabbing most of the capacities. Read Shopify, Wayfair, Etsy Face Higher Holiday Shipping Prices, Shortages.

Indeed, those focused on operating online retail’s infrastructure faced such a peak in demand that they had no choice but to increase prices, thus improving profitability. Check out Pandemic May Be Best Thing to Happen to FedEx and UPS.

Still, FedEx and UPS’s victory may be short-lived, because many people (both entrepreneurs and financiers) are already hard at work automating logistics to be able to scale up capacity and match rising demand: As E-Commerce Booms, Robots Pick Up Human Slack.

Meanwhile, many traditional retailers have gone down because they were too middle-of-the-road to be able to withstand the shock of the pandemic and customers no longer visiting stores. Case in point: Macy’s and J.C. Penney.

Some traditional retailers and shopping malls going down provided others with additional storage capacities. But who among the winners was able to profit from this? You guessed it: Amazon Warehouses in Ex-Sears Stores Makes Curbside Sense.

Only a few traditional retailers have been able to survive. Walmart is doing well (it’s the leader after all, so it tends to win in the context of Darwinian Economics). Target is also a COVID-19 winner. Also check out Best Buy Earnings: Retailer Fights Harder to Join Pandemic Winners.

What conclusions can we draw from all that in terms of capital allocation? You can sketch some kind of growth-share matrix (here for the US market):

Stars. That’s a one-company category: Amazon. It will only get stronger as the shift progresses, including by expanding into physical retail. (By definition, the Entrepreneurial Age is “winner takes most”, and so Amazon is the lone star.)

Cash Cows. That’s definitely Walmart, because it’s the leader on the legacy segment of the market: as such, it will always come out on top. Then there are those operating the infrastructure made scarcer/more relevant by the paradigm shift (FedEx, UPS): Buy, then hold.

Dogs. That’s Macy’s and J.C. Penney, the ones that should be divested. And if you had seen it coming, you should even have shorted them. Now you can buy their assets and turn them around to repurpose them to serve the transition (like by leasing the space to Amazon).

Question Marks. Shopify could be a star... if it wasn’t fighting against Amazon for precious shipping capacity, so it’s still a question mark. Also there are legacy retailers that have succeeded at strategic positioning (Target), as well as those companies building the warehouse robots.

There’s a pattern here, and it’s been revealed with the pandemic as an accelerating factor. My thesis is that the paradigm shift follows the same pattern across industries. What it means is that what you’ve learned by observing the retail industry in the pandemic, you can apply in other industries even if the shift takes longer. Ain’t that an inspiring thesis for a hedge fund?

More writings on capital allocation:

😥 VCs Reading David Graeber

Last Monday I was wondering if the late David Graeber was well-known in the US. Indeed, it seems he is: I have spotted articles in all outlets I’m monitoring on a daily basis. Even better, Alex Danco, who as you remember works a lot on debt financing, paid tribute to Graeber on Sunday due to his masterful work on the history of debt. Read it here: Scarcity Status versus Abundance Status (Gift Culture Part 3).

Debt: the first 5000 years (which I wrote about in this newsletter several months ago) is an enormous, sweeping look at the human history and anthology of Money, Debt, and their two-sided relationship. (The best books about money theory are written by the communists.) If you never read my original post from a few months back, please do that.

👎 Enough With Localism

I’ve had this idea for several years now: in the Fordist Age, the only way to approach users in a customized way was to decentralize operations. But now, in the Entrepreneurial Age, customization is mostly driven by data and algorithms, and so it’s much better to centralize operations.

For instance, Facebook is probably one of the largest centralized organizations on Earth, and yet its product is rather different from one user to another. On the other hand, while the French school system may be highly decentralized, it still feels like a one-size-fits-all product; and its legacy decentralization makes it impossible to deploy large databases and run powerful algorithms so as to customize the online experience (which is non-existent anyway).

I wrote about this in the context of business here: Data Eats Brand for Breakfast. And it all came back to me recently after reading Out of Pocket’s Healthcare should NOT be local.

🇫🇷 Don’t Fall for France’s Industrial Policy

I admit I tend to be harsh on my home country, probably because I know it too well. But I’ve seen all the articles and praise about Macron announcing a €100B recovery plan ($), and I must say I’m not convinced. In particular, a dedicated government agency has been founded (the Haut Commissariat au Plan), which is an echo of the legendary agency founded right after WWII and headed by a visionary named Jean Monnet. As my wife and I discussed earlier this week in a podcast conversation in French (as part of our small family media operation Nouveau Départ):

Jean Monnet was essentially put there by the US. He was close to some of the legendary “Wise Men” (Averell Harriman, Dean Acheson) and had contributed to designing the Marshall Plan. He was the one the Americans could trust with their money when it came to planning reconstruction in France. Hence Monnet became the first Commissaire au Plan.

These days, however, it’s not about reconstruction: it’s about catching up on the US and China when it comes to building tech companies, and then accelerating economic development in a paradigm that is clearer now, but that the people in charge still don’t understand. (I wrote about a potential roadmap in Europe Is a Developing Economy.)

You might say it doesn’t matter. Let the government throw the money out there, and innovators and financiers will take care of the rest. Except it’s more complicated than that. This could be the playbook for a country that’s at the frontier and can accept a lot of waste—big government agencies, but not much planning, as was the case in the US during WWII. France, however, is a follower more than a leader, which means it needs effective planning (because catching up only comes with a clear indication of where we’re headed), as well as the right persons in charge—people like Deng Xiaoping, Vannevar Bush, Harold Ickes, or Jean Monnet. And I’m afraid that’s really not the case at the moment—see what I wrote in the FT in 2018.

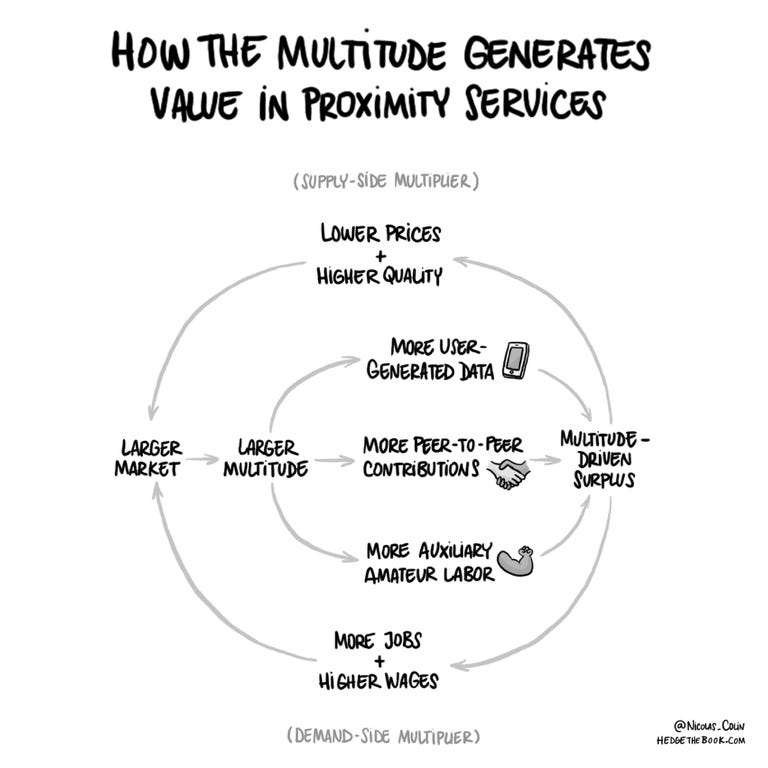

📉 Proximity Services

Finally, I was interested in this work by David Autor and Elizabeth Reynolds about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lower end of the labor market. Basically, as the subtitle suggests, we’ll come out of this period with Too Few Low-Wage Jobs: The Nature of Work After the COVID-19 Crisis.

The paper goes into the details, but we can already guess the two main reasons:

One is hysteresis. Many businesses in proximity services have taken such a hit, they would need time to reopen (or for resources to be reallocated); meanwhile consumers will have switched to a new way of life that involves many fewer low-wage jobs.

The other reason is automation. Every major economic crisis is followed by surviving businesses doubling down on increasing productivity, which translates into fewer jobs created for the same level of output. The robots might be coming after all, bringing economic growth!

The scarcity of low-wage jobs will no doubt contribute to increasing social unrest and political tensions. But there’s also good news: it means many sectors that were stuck in a low-productivity trap for lack of innovation will now race ahead, adding a lot of value to the economy and making it possible for forward-looking governments to harness that macroeconomic surplus and create low-wage jobs elsewhere. In the meantime, we might finally see what tech-driven proximity services look like 😉

(Below is an illustration from my book Hedge by Marguerite Deneuville.)

If you’ve been forwarded this paid edition of European Straits, you should subscribe so as not to miss the next ones.

From Normandy, France 🇫🇷

Nicolas