Business Strategy at a Small Scale

Today: I long thought that business strategy only applied to large, mature businesses. That’s not true anymore.

The Agenda 👇

Startup founders should focus on product, not strategy

Meanwhile, business strategy is being commoditized

It now applies to small businesses and even individuals

More capitalism, less market economy

A new strategic paradigm: uncertainty

We have a joke at my firm The Family. Back before the pandemic, we used to hold weekends in the countryside to welcome the startups that had recently joined The Family. I admit I didn’t attend because I lived in London at the time and I have children, so weekends away were quite scarce.

But occasionally a founder would ask “But where is Nicolas? I’d love to meet him.” And my cofounder Oussama Ammar would respond:

He’s not here, because if you start talking to him, soon it’ll all be about corporate finance and business strategy, which aren’t at all relevant to your startup. You need to work on one thing and one thing only: your product and making sure that it’s something people want.

For a time I kind of adhered to this idea that business strategy doesn’t really matter at an early stage or a small scale. Business strategy, after all, is all about strategic positioning—and by definition such positioning is only possible if you have multiple leverage points.

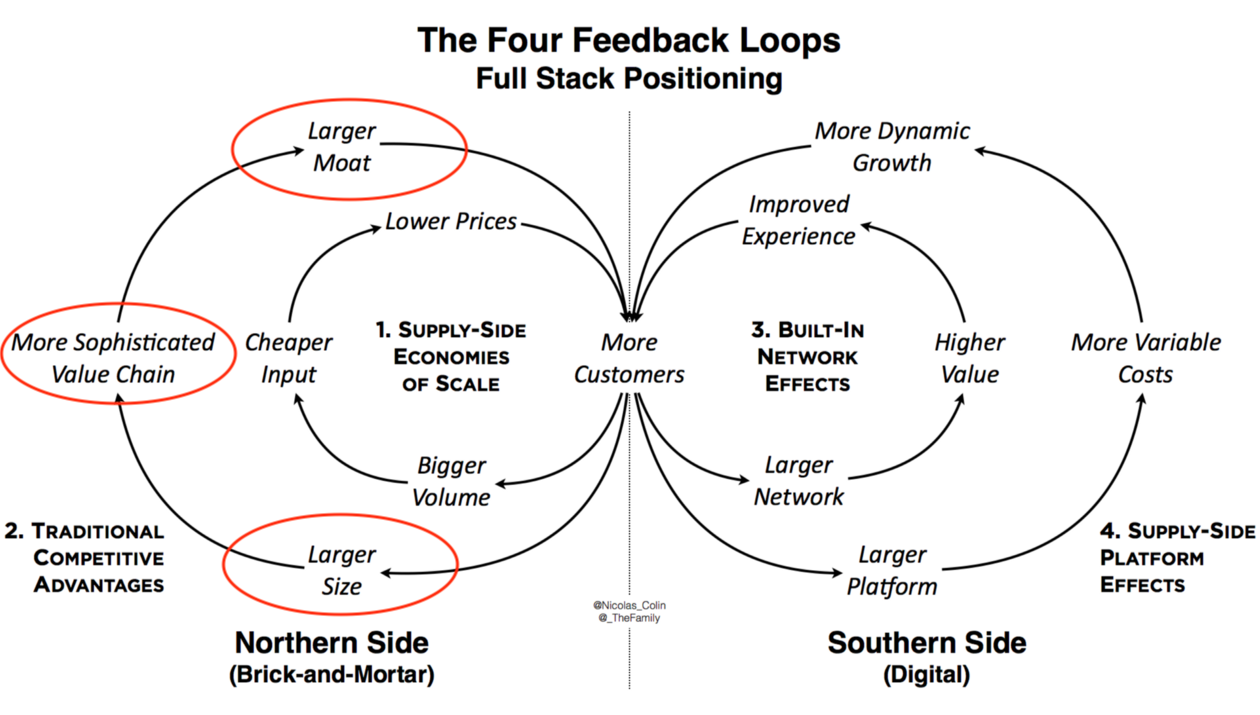

Therefore it’s better to have a somewhat complex and distinctive value chain, which only exists at a large scale, as explained in this graph from 2016:

However, more recently I’ve come across four (intellectual) trends suggesting that strategy is about to become an important thing for small companies as well, and even individuals.

The first is the incredible proliferation of blogs and newsletters dedicated to business strategy. Back in 2015 and 2016, I had the impression of being part of a very small group of people trying to apply the lessons of traditional business strategy to the digital world—existing in the shadow of giants such as Ben Thompson of Stratechery and, well, not many others.

Today, business strategy seems to be the most enjoyed topic by online writers, with dozens of in-depth company profiles like the ones I once dedicated to Amazon, Goldman Sachs, Lego, and Warner Music, and emerging popular authors like Nathan Baschez, Brett Bivens, and Packy McKormick. And that’s without even mentioning the ones working on a crossover that I love, that of strategy and finance: check out Patrick O'Shaughnessy and the founding father of that approach, Michael Mauboussin. (One other influential author who, in my eyes, seems to have emerged only recently: Hamilton Helmer, author of the book Seven Powers.)

So (almost) everyone is into strategy these days, which makes it even more difficult to break through if, like me, you have ideas to share in that field. Strategic thinking has been commoditized! Of course, that’s quite a paradox if you realize that the most obvious approach to strategic positioning is… differentiation.

Second, an interesting phenomenon that’s correlated with the commoditization of business strategy is the fact that the discipline, once exclusive to large organizations, now applies to small businesses—even individuals. It’s one of the core messages of Adam Davidson’s inspiring recent book, The Passion Economy—or, as once explained by Seth Godin:

Building trust and connections are the hard (and necessary) part of marketing today. We’ve reached a point in our evolution where differentiation matters more than ever because mass marketing no longer cuts it. When we’ve standardized everything to the point that the main differentiator is price, then it’s a race to the bottom.

As illustrated in worlds as different as Substack, Patreon, Sellsy, OnlyFans, and many others, success can be found not by trying to do the same thing as the others, only better or cheaper, but in finding your own niche and digging deeper so as to position yourself on a market that nobody else will dare enter. And what’s that if not business strategy applied to the craft of individual creators!

Third, this echoes one of my major (personal) discoveries of the year 2019: the difference, as documented by French historian Fernand Braudel, between the “market economy” and “capitalism”. As I wrote in Capitalism and the Future of Nation States,

The economy can be subdivided into three categories. The first, which he calls “material life”, is made up of the infinite, informal transactions that form our daily lives. The second, the “market economy”, is where individuals conduct business, establishing a link between production and consumption. The third, finally, is “capitalism”...an ensemble of processes that allow one to extricate oneself from the trivialities of commerce and pursue increasing returns to scale. The market economy is the world of merchants, those who buy and sell while taking a small margin as items pass through their hands. Capitalism, on the other hand, is the world of the traders, financiers, and entrepreneurs who...attenuate the rigorous competition in the market economy by “inserting” capital into the production process.

The connection of the idea above with the world of early-stage startups was revealed in a Paul Graham classic, Startup = Growth:

For a company to grow really big, it must (a) make something lots of people want, and (b) reach and serve all those people. Barbershops are doing fine in the (a) department. Almost everyone needs their hair cut. The problem for a barbershop, as for any retail establishment, is (b). A barbershop serves customers in person, and few will travel far for a haircut. And even if they did, the barbershop couldn't accommodate them.

Writing software is a great way to solve (b), but you can still end up constrained in (a). If you write software to teach Tibetan to Hungarian speakers, you'll be able to reach most of the people who want it, but there won't be many of them. If you make software to teach English to Chinese speakers, however, you're in startup territory.

Most businesses are tightly constrained in (a) or (b). The distinctive feature of successful startups is that they're not.

It’s quite straightforward! The barbershop is part of Braudel’s “market economy”: there’s not much room for strategic positioning in the barbershop business, where the health of your business mostly depends on the location of the shop. Conversely, a startup is clearly playing the game of capitalism—willing to lose money (= deploying capital) for as long as it takes in order to generate increasing returns to scale and enjoy the exponential growth that sets them apart. In doing so, they’re using strategic positioning.

Which brings me to my fourth point: There is now a school of thinking when it comes to strategy applied to early-stage startups, and I think we should call it the school of uncertainty! Two authors in particular stand out in that realm.

One is Vaughn Tan, whose work was discussed not long ago by my wife Laetitia Vitaud. Here’s a quote from Vaughn’s The Uncertainty Mindset (discussed in this podcast with Laetitia):

There is a fundamental difference between [risk and uncertainty] that must be understood (...) The work risk means that the exact future that will result is unknown, but the different possible futures are knowable in a way that allows you to plan by calculating how likely different possible futures are and taking clearly sensible actions based on those calculations. (...) True uncertainty is uncertainty that cannot be measured and cannot be eliminated using strategies chosen based on likelihoods of outcomes. (...) The existential threat from true uncertainty can undoubtedly be terrifying, but it also represents opportunity for innovation. Where the future is uncertain, people and organizations have to influence what it becomes.

The other is Jerry Neumann, about whose inspiring essay Productive Uncertainty I’ve written several times over the past weeks, notably in On Jerry Neumann's “Productive Uncertainty” (Round 1). Here’s a quote from Jerry’s essay:

Questions asked about things that are uncertain can not be answered, but these questions can be asked even if the eventual product and market are not entirely clear because the two types of uncertainties give such different answers. These answers should guide product and market strategy and be updated as these strategies progress. The goal of the strategy-making process is to determine the most protectable manifestation of the company’s innovation, which moats can be put in place, when they need to be in place, what needs to be done to build the moat, and how these activities can be intertwined with the designing, building, and commercializing of the product.

Go further by reading my December essay All About Risk and Uncertainty 👀

As you might remember, The Family has now pivoted to a fully remote model, whereby we work with a batch of 25-50 startups several times a year. One of the contributions I make to that key part of our business is hosting Friday online conversations with inspiring thinkers and practitioners in the field of business strategy. Over the next few weeks, I’m honored to host Vaughn Tan, whom I quoted above, as well as my old friend Ben Robinson of Aperture, with whom I’ll talk about “Business strategy for early-stage startups”—an idea in which I’m now a firm believer!

I’ll make sure to share more along the way. In the meantime, what do you think?

If you’ve been forwarded this paid edition of European Straits, you should subscribe so as not to miss the next ones.

From Munich, Germany 🇩🇪

Nicolas

I just received The 7 Powers today in my house, that is what I call a timely post!

I have been working at the same intersection (strategy-finance-innovation) for twenty years (in Healthcare and Life Sciences) and never I heard before reading it from you about Hamilton Helmer!! (Ignorance as a blessing).

In the healthcare industry, strategy is very relevant for startups (early stage or small scale), mainly for Biotech and MedTech, where decisions on what activities to perform and which not in your value chain are critical to the success of the startup. Whether to do R&D (or buy it), design (or buy it), distribution (or buy it), etc.

I would like to add another reference for "thinkers applying strategy to early-stage startups": Joshua Gans and his article in HBR in 2018, which includes a tool/matrix called "The Entrepreneurial Strategy Compass" with four distinct strategies.

https://hbr.org/2018/05/strategy-for-start-ups

Last time I asked him, they were writing a book on “Entrepreneurial Strategy" which was planned to be published by late 2021.

Some additional information: https://www.entrepreneurial-strategy.net/