Hi, it’s Nicolas from The Family. Here’s the first round of a discussion of how buyout firms are making inroads in financing tech companies—and the lessons we can draw.

What follows is an initial collection of my thoughts about private equity becoming more prominent as a source of funding for startups and tech companies. By private equity, I mostly mean buyout firms—that is, firms with funds under management that deploy capital as both equity and debt, in variable proportions, preferably in companies that are already profitable and can thus generate a dividend to pay down the debt. I know that venture capital technically belongs to the larger category of private equity, but here I’m referring to the likes of Silver Lake, Vista Equity Partners, and Thoma Bravo rather than Sequoia, Andreessen Horowitz and Index Ventures. At this point, I have no other purpose than to share general ideas as to why private equity might be the future of funding tech companies in Europe.

1/ Let’s start with a very short history of private equity. The early history of funding businesses was mostly about debt, followed by the introduction of joint stock companies in which members of the public could invest by buying shares, followed by the rise of private equity. Here’s what I wrote in 2016 in A Brief History of the World (of Venture Capital):

The first half of the 20th century saw investment opportunities extended to two categories of ventures: those that deployed valuable tangible assets (railroads, later telcos) and those that operated a retail business (such as Goldman Sachs’s client United Cigar). Before World War II, banks and the public would buy shares in or lend money to companies with tangible assets or a recurring revenue derived from a retailing business.

The problem is that technology-focused entrepreneurial ventures didn’t fall into either category. They couldn’t borrow from banks because their business model was unknown and they still had everything to prove. And they couldn’t raise capital from the public because no financier could value them. This gap led to the emergence of private equity: because it was so risky, technology ventures were forced to rely on wealthy individuals. In some cases those were syndicated by a merchant banker, who co-invested with his clients. But those deals usually failed to generate enough money to finance very ambitious ventures—except if they were carried out by exceptional financiers such as Lazard’s André Meyer or Warburg Pincus’ Lionel Pincus.

This perspective is interesting: it reveals that private equity was initially born to fund tech companies—to fill the gap between public markets and lending institutions. It’s only later that private equity drifted away and started funding companies that were more mature, better understood, and profitable.

2/ The history of leveraged buyouts is quite murky as there are many precedents of combining equity and debt in a sophisticated way that can be traced back to various periods of history. But it is widely admitted that buyouts as we know them these days were pioneered sometime in the 1970s by people like Jerome Kohlberg (the first “K” in “KKR”). As explained by Wikipedia,

The industry that is today described as private equity was conceived by a number of corporate financiers, most notably Jerome Kohlberg, Jr. and later his protégé, Henry Kravis. Working for Bear Stearns at the time, Kohlberg and Kravis along with Kravis' cousin George Roberts began a series of what they described as "bootstrap" investments. They targeted family-owned businesses, many of which had been founded in the years following World War II and by the 1960s and 1970s were facing succession issues. Many of these companies lacked a viable or attractive exit for their founders as they were too small to be taken public and the founders were reluctant to sell out to competitors, making a sale to a financial buyer potentially attractive.

3/ In fact, two trends made it easier and easier to implement such deals from the 1970s onward. One was that many businesses founded in the age of the automobile and mass production were reaching a point of exhaustion at that time:

Western European countries and Japan had completed the process of catching up on the US following World War II. This translated into a more heated competition on many markets, forcing companies to trim margins and double down on improving the quality of their products. Most firms were still profitable but they had to learn to get leaner and faster. Private equity brought the capital and the know-how to help managers do just that.

Meanwhile, continuous improvement in managing supply chains and various other functions in the corporate world (including thanks to a new trend known as globalization) were creating unprecedented opportunities to downsize the workforce, redeploy operations, streamline value chains, and other things. The problem is that most firms lacked the necessary pressure to reach what were rightfully considered as tough decisions.

And so private equity firms were bringing something else to the table: a powerful incentive to generate additional productivity gains, which took the form of debt used as leverage. Companies had to pay steady dividends to return the money borrowed to fund them. That financial burden became a powerful lever to force radical change on the way these companies were organized and managed.

4/ Another trend that explains the rise of private equity, especially from the 1980s onward, is the upheaval of the financial services industry, which made it easier to borrow the money and fund larger and larger deals. Michael Milken, the founding father of high-yield bonds (also known as “junk bonds”), brought about radical change on that front. As written by Jeff Madrick in Age of Greed (an excellent book about the recent history of finance, contrary to what the title suggests):

[There was such a thing as the] Milken magic. He could now almost create money, enormous sums of money, at a moment’s notice. By 1984, Wall Street was put on notice that he had a buyout fund of billions of dollars that he could make available almost immediately to takeover impresarios. It was the beginning of a historic relationship between Milken and KKR, which went on to dominate LBOs, culminating in the largest to that point, a $25 billion takeover of RJR Nabisco that made headlines daily in 1988 and early 1989.

As time went by, established buyout firms ended up having access to so much capital, brought about by enthusiastic counterparties in the institutional world, that they decided they had to diversify. As an example, Blackstone expanded in real estate (and is now the largest owner of corporate real estate in the world), and KKR became a player in lending.

Both trends (the age of the automobile and mass production reaching maturity and massive amounts of available capital) accelerated in the following years. In part, there was a causal relationship between them: it’s because of the exhaustion of established firms that investors had so much capital on their hands and were all too enthusiastic about allocating it to private equity; in part, there were exogenous causes (or maybe not that exogenous 🤔) such as the financial crisis in 2008 and the resulting influx of capital thanks to quantitative easing. In any case, private equity has now become a huge asset class, with a lot of dry powder that investors don’t really seem to know what to do with.

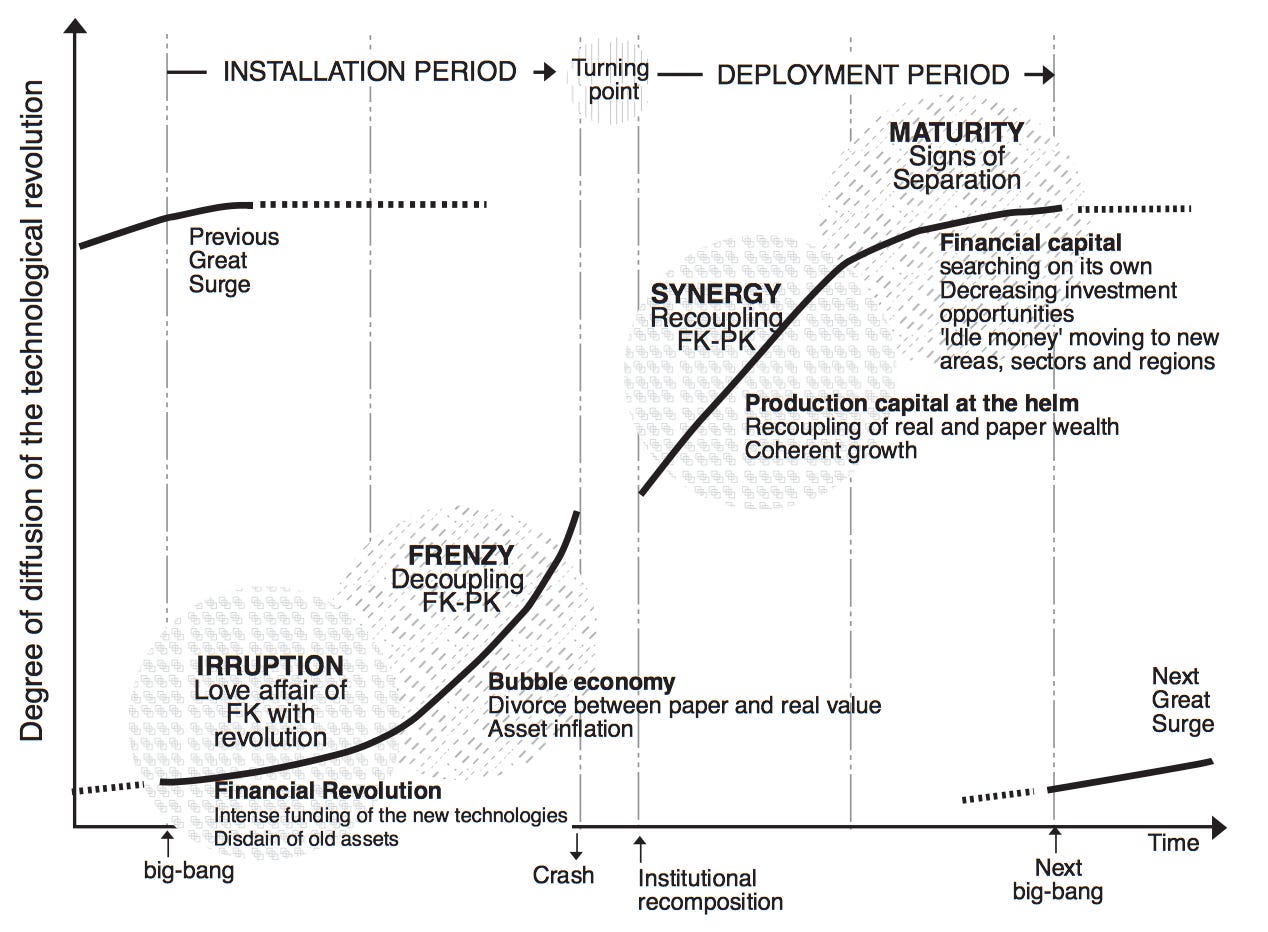

5/ An interesting thought: this could be predicted by readers of Carlota Perez—and there are a lot of them in the tech world. When a “great surge of development” reaches its maturity phase,

In the world of big business, markets are saturating and technologies maturing, therefore profits begin to feel the productivity constriction. Ways are being sought for propping them up, which often involve concentration through mergers and acquisitions, as well as export drives and migration of activities to less-saturated markets abroad. Their relative success makes firms amass even more money without profitable investment outlets. (p. 55 of Carlota’s Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital.)

Financial capital accompanies the most powerful firms in their attempt to prop up their threatened profits. These firms have by now become huge and are facing increasing difficulty in finding fruitful investment for their mass of profit. This pushes them into buying up smaller competitors to increase market share. (p. 81)

6/ I think there are two factors that explain the piling up of financial capital in private equity as opposed to other asset classes as we enter the Entrepreneurial Age:

There is a kind of hands-on approach to private equity. Raising money from investors through the stock market is the right thing to do for an executive that knows what they’re doing and is ready to do what it takes to deal with the current situation. For most firms, alas, you need the extra-pressure beyond activism in boardrooms: you need the burden of that debt as an incentive to generate those last gasps of productivity that your business still has in it.

As I wrote in my What’s Happening With the Stock Market? (echoing this article in the New York Times as well as Michael Mauboussin’s research), there are fewer and fewer listed stocks, and you can’t count on being exposed to the whole economy if you invest only on public markets. So lots of money chasing a dwindling number of public companies that perform well explains both the inflation in public equities and the accumulation of capital in private equity.

And then there’s a vicious cycle: the more stock prices go up, the more the P/E ratio makes stocks unattractive (see Shawn Tully’s Stocks Are Now Shockingly Expensive by Every Measure—and that was even before the pandemic and the recent rally!), which leads allocators to express even more interest in private equity. It’s good for earning hefty fees, but it also explains all the dry powder that buyout firms are only starting to use these days.

7/ Now, what about tech? (I told you this was a rough draft 😉) Well, I’m sure we all have the impression that IPOs are coming back, with the likes of Vroom (which just went public), Lemonade (which has just filed for an IPO), and Airbnb (where there’s talk of an IPO again, after the shock of the pandemic). Still it’s not that easy: there are still the regulatory barriers, and there’s the dread inspired by the poor performances of the likes of Uber (which is understandable) and Slack (which is harder to explain considering the boom of remote working). Many tech companies, however mature, prefer to remain private for the moment.

What should happen when those tech companies are still private and yet have cap tables harboring early-stage investors anxious for an exit, while at the same time there are those private equity firms sleeping on giant piles of money like the dragon Smaug? A match—and those firms redeploying their funds and upgrading their investment techniques so as to be able to make deals in the tech sector. And the reason I’m interested in this is because maybe it could be a solution for the lack of a clear path to exit for investors in European tech companies:

Despite the recent uptick, IPOs are getting scarcer in the US, too. And so how have US venture capitalists managed over the last 10 years? By supporting the rise of an alternate ecosystem of secondary investments, which has seen mutual funds, hedge funds, large private equity funds, and various special purpose vehicles take over and provide early, sizeable returns.

Can Europe pull the same trick? It has all it needs to succeed: local ecosystems building up; lots of capital in search of returns; a financial services industry now distributed across London, Paris, Frankfurt, Luxembourg, and Zurich; pioneering efforts with firms like Balderton raising late-stage liquidity funds; and governments determined to make it happen.

8/ There are abundant signs that it really is happening—maybe not too much yet in Europe, but definitely at the global level. Established private equity firms are ready to invest more in tech companies. Let’s have a look at my Evernote database (I have a tag called ‘VC-PE’):

Two years ago, Pitchbook’s Kevin Dowd was writing that “at a growing rate, private equity firms are backing companies at earlier stages than normal in pursuit of a windfall. The past five years have brought an explosion of PE investment in unicorns, per PitchBook data, with deal count quadrupling and the value of those deals expanding at an even more extraordinary rate.”

In September last year, there was an article in The Financial Times about “KKR, the alternative investment company whose name has long been synonymous with buyouts, taking concrete steps into the world of early stage investing. It is considering plans to raise a $300m Technology, Media and Telecommunications fund for Asia, according to people familiar with the matter, supplementing its $9.3bn Asia buyout fund — one of the region’s largest.”

Same with Blackstone (in TechCrunch, also in September 2019): “We’re capital-preservation minded while looking for asymmetric upside, and that’s where we have a disproportionate advantage. You’ll see us do deals where we can put our thumb on the scale, because of our real estate holdings or buyout assets or because [search across our] portfolio for help with procurement costs or insurance or R&D or a company’s go-to-market strategy.”

As could be read in Institutional Investor back in February, “The number of private equity buyouts of start-ups funded by venture capital grew at an annual rate of 18.1 percent between 2000 and 2019, according to PitchBook.”

Then when Airbnb raised $1B from Silver Lake in the middle of the pandemic, Bloomberg’s Alex Webb wrote that “as equity markets tumble, private market valuations are also falling. And as companies need cash to see themselves through the crisis, ready access to capital is also drying up. That’s creating windows for private equity funds to invest under more favorable conditions.”

Finally, in a very recent edition of is newsletter Sunday CET, Dragos Novac mentions the fact that “EQT competed with other PE houses like KKR [for acquiring Spanish company Freepik] and did the deal by itself and not through its VC arm”. The price was €250M.

9/ The presence of private equity firms in the tech world is nothing new. What’s more difficult to decipher, however, are the underlying strategies and how they’ve evolved over time. I have several cases that I’m currently studying in preparation for an “11 Notes on Silver Lake”:

In his book Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy, Warburg Pincus’s Bill Janeway described a deal he made to invest in Zilog Semiconductors, a microprocessor company that excelled on the technical side but was later beaten to the market by Intel. A decade later, however, one of Bill’s first successful IT investments was “to back a management team that knew how to apply Zilog’s legacy technology to low-cost consumer electronics. Jointly, we constructed the first ever leveraged buyout of a technology company”—acquiring Zilog from Exxon Enterprises.

Later in the book, Bill describes the launch of “OpenVision Technologies with a commitment to fund up to $25 million on terms agreed in advance. If this line of equity were fully drawn, we would own a share of the company determined up front, the founders would own their agreed share, and both would be diluted by a pool of stock options reserved in advance for future employees. The equity line of investing structure was an innovation, constructed in direct contrast to the traditional venture capital funding model of multiple rounds of investments with multiple firms investing per round…Warburg Pincus had the cash to fund a venture such as OpenVision, but it only made sense to do so if we had unequivocal control. Delivery of funds under our commitment had to be entirely at our discretion. Our approach did give up the external market test represented by the willingness of other firms to invest, but it was subject to the regular scrutiny of all the partners of the firm, each of whom had a keen interest in the state of play.” This is far from traditional private equity, yet it’s also very different from venture capital.

Finally, there’s Silver Lake itself, which has been in the news quite a lot recently—with landmark deals with Expedia, Airbnb, Reliance Jio Platforms in India, and others. The firm’s history is particularly interesting, contributing to why I’ve decided to dig in and prepare an “11 Notes” article that will be published in a few weeks. What especially interests me is how Silver Lake went from “chasing overlooked but cash-generative castoffs of technology trends gone cold” to backing the symbol of cash-burning tech unicorns that is Airbnb. It’s a mystery I intend to solve because I think it’s the key to understanding the current funding landscape and how we can guide European tech companies toward more liquidity 🇪🇺

10/ Eventually, I’m sure, we’ll witness some kind of convergence between venture capital and more traditional private equity. While public markets run amok (again, too much money chasing too few stocks), many things are happening on private markets:

The fact that SaaS revenue is easier to predict is inspiring a lot of thinking around financing such companies through debt and revenue-based securities. This discussion was perfectly framed in January by Alex Danco’s Debt Is Coming (actually building on Carlota’s and Bill’s work).

Value investors are in disarray as they struggle to perform when compared to growth investors. This has triggered quite a lot of challenging discussions, from which new approaches and new techniques might arise when it comes to assessing value.

The more you read about the topic, the more you realize there are indeed many buyout firms interested in technology. Yet those guys (and yes, it’s almost all guys) don’t communicate as much as venture capitalists, and so understanding what they have in mind is quite a challenge.

What do you think? Have you encountered any interesting practices in the private equity world? Do you have sources that can help me better understand Silver Lake’s strategic shift? Please reach out and let me know! There are few topics that are as important and as interesting at the same time 😉

From Normandy, France 🇫🇷

Nicolas