Hi, it’s Nicolas from The Family. Today, I’m pursuing my reflections on capitalism and discussing new approaches to align the interests of a corporation’s shareholders and customers.

⚠️ First of all, don’t miss my latest column in Sifted, in which I discuss the evolution of venture capital. As software eats the world, we need venture capital at a larger scale. But since the economy is complex and diverse, venture capital is now moving in many different, potentially diverging, directions—and it makes it more difficult to grasp as an industry. Read it here: The Fragmentation of Venture Capital ⚠️

🇨🇭 Apart from that, I just spent two days in Switzerland, first to visit my friends Ben Robinson and Dan Colceriu of Aperture (and record a podcast which should be released soon 📻), and then to participate in a discussion yesterday at Davos about the future of work. The focus there was on the resilience of regional labor markets—that is, what we should change so that regional economies are more able to rebound in a context of continuous technological change and corporate fragility.

As for today, I want to pursue my reflection on capitalism, sharing with you a fourth issue of what will likely be a five-part series. As a reminder, here are the previous ones:

Capitalists Beat Merchants Everytime is about the difference between capitalism and the market economy, and the implications from a financial perspective.

Give Capitalism a Chance makes the case that as a three-player game, capitalism is the best system for generating a surplus and developing the economy.

Capitalism and the Future of Nation States revisits the issue of capitalism through a lens provided by the French historian Fernand Braudel.

Now I’d like to dive into the current discussions about sharing the surplus generated by a corporation with its various stakeholders, notably its customers. Read along 👇

1/ In any techno-economic paradigm, capitalists have but one goal: generating increasing returns to scale so as to escape the rigors of competition.

In the 20th-century Fordist Age, the best position for generating such returns was to combine standardized parts (or tasks) with scientific management. Hence the 20th century saw the rise of corporate giants primarily in manufacturing and some capital-intensive service sectors.

In today’s Entrepreneurial Age, increasing returns still exist in manufacturing (up to a certain scale), but they are more easily sustained when interacting with a large number of individuals connected to one another through a network. I call such networked individuals the “multitude”.

2/ Any entrepreneur interested in doing capitalism in any sector can harness the power of the multitude, that is, they can generate increasing returns to scale through demand-side network effects. Amazon, for example, does it in the very tangible business that is retail, as explained by Tim O’Reilly:

Unlike eBay, whose constellation of products is provided by its users, and changes dynamically day to day, products identical to those Amazon sells are available from other vendors. Yet Amazon seems to enjoy an order-of-magnitude advantage over those other vendors. Why? Perhaps it is merely better execution, better pricing, better service, better branding. But one clear differentiator is the superior way that Amazon has leveraged its user community… Amazon doesn't have a natural network-effect advantage like eBay, but they've built one by architecting their site for user participation. Everything [...] encourages users to collaborate in enhancing the site... Amazon's distance from competitors, and the security it enjoys as a market leader, is driven by the value added by its users.

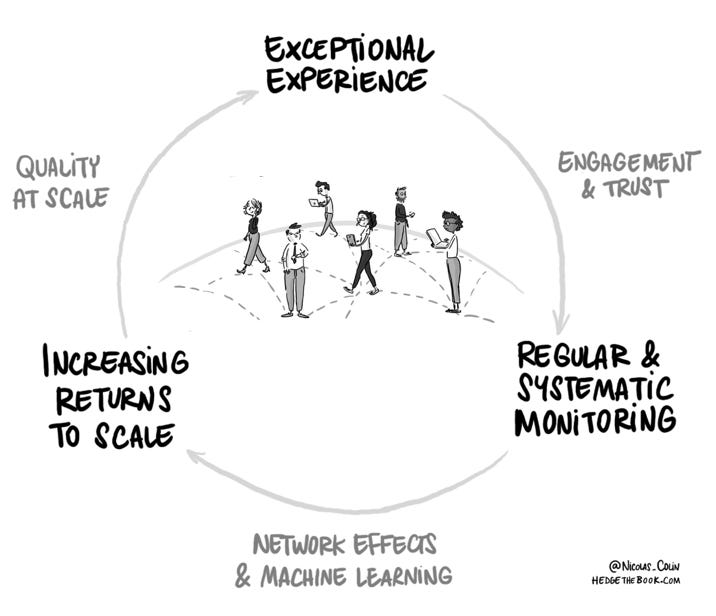

3/ The concept I use to describe the relationship between today’s successful capitalists and the multitude is that of an alliance. Users won’t contribute to generating increasing returns in exchange for nothing. They want something to reward their effort. This is why Jeff Bezos is so ruthlessly focused on Amazon’s customers (except when it’s Day Two). He knows that those precious increasing returns that make him a successful capitalist are only granted in exchange for Amazon taking extremely good care of its customers. The exceptional customer experience is what fosters trust and engagement, which in turn makes it possible to generate network effects and then to improve quality at scale.

4/ The rise of computing and networks has thus triggered a rebalancing of the unspoken corporate contract between shareholders, employees, and customers. As a reminder, this contract determines how a corporation’s surplus is divided between the three groups—whether that’s higher proceeds for shareholders, higher wages for employees, or lower prices for customers:

Back during the postwar boom, employees had the upper hand. Their loyalty and effectiveness along assembly lines was absolutely critical for large manufacturers to succeed at doing capitalism. Thus workers had to be rewarded with higher wages and better benefits.

During the age of financialization that followed (from 1968 to 2008), shareholders got their revenge: by leveraging voice (through corporate governance) and exit (the constant possibility of divesting or forcing a company to relocate its production abroad), they managed to bring wages and benefits down and to claim a larger share of the surplus generated by corporations.

Now in the Entrepreneurial Age, customers finally have the upper hand. As the multitude, they’re able to use technology to claim a higher proportion of the corporate surplus under the form of quality at scale (a widespread, upgraded version of Charles Fishman’s “Wal-Mart Effect”).

5/ There’s a large toolbox that corporate executives can choose from to strengthen their corporation’s alliance with the multitude:

As I wrote in a previous issue, the most traditional tool is the counter: hence the Apple Stores and Amazon acquiring Whole Foods. Then there’s financing: it’s no coincidence that we’re witnessing every tech company morphing into a bank. And then there’s obviously building a brand.

Yet there’s a tool whose power and effectiveness now surpass that of all the others, and that’s collected data. At the level of an individual customer, it makes it possible to personalize the experience and increase loyalty. At the aggregate level of all customers, it contributes to revealing flaws in your product and inspiring product managers and designers in their efforts at constantly improving the user experience. Indeed, monitoring user activity on a systematic and regular basis has become the main generator of increasing returns to scale.

6/ At some point, however, even data and network effects are exhausted as a lever for strengthening the alliance with the multitude and gaining a competitive edge. There are many reasons for that: the talent shortage (it’s more difficult to hire at scale); the heaviness and rigidity of large organizations (it’s easier to innovate in a small startup than at, say, Google); there’s a thing called reverse network effects; and then trust is fragile. And that’s what leaves even the most successful capitalists vulnerable.

What happens once everyone on the market excels at designing applications, collecting data, orchestrating network effects, and innovating on a continuous basis? At this point, capitalists have to explore new approaches. Airbnb is inviting stakeholders into its governance, as discussed by Matt Levine here. BlackRock is warning corporate CEOs that they will have to comply with society’s demand for action against climate change. Corporations such as Casper and Etsy are positioning themselves as movements so as to further leverage the power of their customers.

But there’s yet another line of thought that I find promising when it comes to aligning the interests of a corporation and its customers: Once you’ve reached peak quality at scale, can you distribute an even larger share of the corporate surplus to your customers by effectively turning them into shareholders?

7/ The context here is the scarcity of companies going public. These days, going public happens much later in the history of a corporation—if it happens at all! There’s so much capital on private markets that the regulatory price one pays with an IPO is simply not worth it. As a result, individuals have fewer and fewer opportunities to claim a shareholder’s portion of the surplus generated by the corporations from which they buy products. As Scott Kupor of Andreessen Horowitz wrote back in 2013,

Over the past decade or so, regulatory changes have reduced the frequency with which the stocks of high-growth companies get offered to the public during their most dramatic phases of growth. That prevents ordinary investors from getting in on the wealth creation, and hampers the creation of middle class jobs...Indeed, we are quickly creating a two-tiered investment market—one for wealthy, accredited individuals and financial institutions and a second for the remaining 96% of Americans.

8/ This problem of capitalism being out of reach for most individuals has not escaped the attention of policymakers and others:

From a policy perspective, there were two attempts in the US at going around the traditional IPO process, both coming from the JOBS Act of 2010. One is so-called Regulation Crowdfunding, but there are issues with adverse selection (the best companies don’t use that tool) and the results have been dismal. The other is known as Reg A/A+ (a.k.a. “mini-IPO”), but it’s too long and too complex for the small amounts of capital that it provides companies with.

Then came the wave of the Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs), which was the technological response to the impossibility for ordinary individuals to participate in the new capitalist feast. The problem is that the barriers to entry were so low that the new process attracted too many scammers, and regulators had to step in, curbing everyone’s enthusiasm and creating many obstacles for implementing ICOs in the process (see the example of Telegram).

9/ Now, Fairmint, one of our portfolio companies, has been working on how to share a larger slice of the surplus with customers—tackling the problem on both legal and technological fronts. What they’ve designed is a new kind of security that facilitates capital formation while protecting the interests of individual investors. Fairmint calls these CSOs, for “continuous securities offering”: a new fundraising approach that makes it possible for growth-oriented companies to raise capital on a continuous basis from anyone who supports their product and mission.

I’m particularly involved because Thibauld Favre, a cofounder of Fairmint, was previously a director at The Family and spotted that particular problem while working with venture capitalists and entrepreneurs. He moved forward by relying on the notion of the multitude as introduced back in 2012, and then on the further developments included in my book Hedge—all to answer this lingering question: Can we design financial instruments to further strengthen a corporation’s alliance with its customers in the Entrepreneurial Age? Well, Fairmint’s answer is positive, and it’s here 👉 Introducing The Continuous Securities Offering Handbook. (Also have a look at this thread.)

10/ By the way, welcoming customers as shareholders is only one dimension of upgrading organizations for the Entrepreneurial Age:

The shape of organizations is changing. In the past, the optimal approach for doing capitalism was to build what I call a cathedral: a pyramidal organization managed from the top down and standardized to the extreme. Today, however, increasing returns are best delivered by organizations that bring together a vast network of connected individuals. I recommend this related article by Floodgate’s Mike Maples: Network-Based Businesses Will Disrupt All Sectors of the Economy.

Technological progress will be more and more about enabling networked/distributed organizations. The rise of crypto protocols has been critical in that regard. You can read my take on Bitcoin in a past issue of this newsletter: Bitcoin: Innovation Hiding in Plain Sight. You may also like to have a look at the recently launched Nakamoto as well as this excellent conference by Balaji S. Srinivasan about network protocols and distributed models: The Network State.

Finally, you’re probably wondering why I didn’t discuss how we can turn workers, rather than customers, into shareholders. Well, that’s because capitalism is a vast subject that I think merits thoughtful discussion, taking one step at a time 😁 However (i) Fairmint’s CSOs can be used to benefit workers as well, (ii) there are many discussions on sharing value with the supply side, such as this one about Uber wanting to give equity to drivers or this one about Airbnb’s hosts, (iii) there are numerous sections of Hedge that let you dig deeper into that particular topic.

Please scroll down for a reading list on aligning interests within the corporate contract.

🇺🇸 I’ll be in the Bay Area from Feb. 1-10. On the first I’ll be speaking about artificial intelligence as part of the Nuit des idées, which is hosted by the French Consulat général in San Francisco (but it’ll all be in English). The following weekend, I’ll be participating in Tim O’Reilly’s Social Science Foo Camp. In between, I’m available for meetings, especially with people with sharp and informed views about how Europe can catch up in the Entrepreneurial Age 🇪🇺 If you’re one of them, please ping me!

Here are more readings about capitalism and aligning interests:

The Age of Customer Capitalism (Roger Martin, Harvard Business Review, January 2010)

Shareholders v stakeholders: A new idolatry (The Economist, April 2010)

Unshackle the Middle Class (Scott Kupor, Andreessen Horowitz, March 2013)

How Humans Became ‘Consumers’: A History (Frank Trentmann, The Atlantic, November 2016)

Is the customer king? (Willy Bolander, Christopher R. Plouffe, Joseph A. Cote and Bryan Hochstein, LSE Business Review, February 2017)

How Online Shopping Makes Suckers of Us All (Justin Fantl, The Atlantic, May 2017)

Data Eats Brand for Breakfast (me, European Straits, September 2017)

Who Ultimately Pays for Corporate taxes? (Richard Rubin, The Wall Street Journal, August 2017)

“Customer First” Healthcare (Bill Gurley, Above the Crowd, December 2017)

Bitcoin: Innovation Hiding in Plain Sight (me, European Straits, January 2018)

Shareholders vs. Stakeholders? No: Customers (Scott Kupor, Andreessen Horowitz, March 2019)

The blurring lines between investing, collecting and consuming (George Henry, Digital Culture, March 2019)

2020 primary: Democrats need to rediscover this forgotten economic idea (Ezra Klein, Vox, May 2019)

How Costco gained a cult following—by breaking every rule of retail (Zachary Crockett, The Hustle, June 2019)

Reassessing Jack Welch's Legacy After GE's Decline (Joe Nocera, Bloomberg, June 2019)

Popeyes & Private Equity (Ranjan Roy, Margins, August 2019)

From Shareholder Wealth to Stakeholder (Aswath Damodaran, Musings on Markets, August 2019)

What Companies Are For (The Economist, August 2019)

Day Two to One Day (Ben Thompson, Stratechery, September 2019)

Protesters Worldwide Are United by Something Other than Politics (Tyler Cowen, Bloomberg, October 2019)

The SEC Really Doesn’t Like ICOs (Matt Levine, Bloomberg, October 2019)

Being a Founder in the Best Time for Consumers (Richard Shea, November 2019)

From Zurich, Switzerland 🇨🇭

Nicolas