How Fred Terman Turned Stanford Into an Entrepreneurial Powerhouse

European Straits | Work in Progress

Hi, it’s Nicolas from The Family. This is a draft essay on how Frederick Terman turned his beloved Stanford University into one of the best entrepreneurial ecosystems in the world.

This week’s free essay was on Brad Feld and Ian Hathaway’s new book, The Startup Community Way—a deep dive into startup communities and entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Now, I have an ongoing conversation with Ian on how startup communities can be assessed by global investors. Can you allocate capital based on an analysis of how a given startup community is doing—and if a healthy entrepreneurial ecosystem exists to support its growth? To lay the groundwork for this important discussion, which is part of my long-term book project called The Entrepreneurial Investor, I decided to draft an essay on how Fred Terman built the Stanford entrepreneurial ecosystem.

This historical precedent is not particularly well-known, yet it is absolutely key for revealing what ecosystem building is all about.

1/ I love this anecdote by Steve Blank, as told in this excellent conference about his Secret History of Silicon Valley.

One of his talks took place at Stanford University, in an amphitheatre that (appropriately) bears the name of Frederick Terman. Yet when Blank suggested a show of hands, asking who knew who Fred Terman was, nobody raised their hand 😮 (For reference, Terman (1900-1982) was dean of the School of Engineering at Stanford from 1944 to 1958 and university provost from 1955 to 1965.)

Well, let’s say that Terman is no less than the founding father of Silicon Valley. Many people attribute this title to William Shockley, one of the Bell Labs scientists who invented the transistor and who later employed Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, Eugene Kleiner, and a few others as CEO of Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory. However there are two reasons to deny the title to Shockley:

First, Shockley was a horrible person who couldn’t hold his dream team together, didn’t do much with the company he founded, and later became a leading proponent of eugenics.

Second, Shockley founded his company in Palo Alto only because it had become a hotbed for building high-tech ventures—and the man responsible for that was...Frederick Terman.

Alas, for some reason, Terman is not as well known as Shockley (who, after all, was the recipient of a Nobel Prize). And when you look for an explanation of how exactly he contributed to inventing Silicon Valley, you either have to dig deep into works such as Steve Blank’s Secret History to find a few details, or you need to read this very thick (and very expensive) book (which I did) to get the full story.

That’s why for many years I’ve been telling myself that we were all missing something in between: a long-form article focused on Terman and the system he developed, which eventually turned Stanford University into the technological and entrepreneurial powerhouse that it is today. And so here’s my gift to all you paying subscribers here at European Straits: a draft essay about what I’ve learned about Terman and the many lessons we can draw from his legacy.

2/ Let me start with a few words about Stanford.

Although it was a developing country for most of the 19th century, the US was not lacking a tradition of academic excellence—largely inherited from Britain and, to a certain extent, Germany. However, all of the excellent American universities—the likes of Harvard, Cornell, Princeton, Yale, and Dartmouth—were located on the East Coast. The West Coast was simply too far away from the institutional center of the country, and back then it attracted adventurers and merchants rather than young people in search of an education.

Stanford University was founded quite late in the 19th century, by an immensely wealthy railroad baron named Leland Stanford who had bought himself a political career (he went on to be a governor of California and a US Senator). Founding the university that (seemingly) bears his name was the result of a tragic turn of events: in 1885, Stanford and his wife lost their only child, Leland Stanford Jr., who died of typhoid fever while travelling in Europe at age 15. His parents experienced such grief at the loss of their only child that they decided to devote a large chunk of their wealth to buy land around the small town of Palo Alto and found a university as a tribute to their deceased son. And this is why the actual name of the university is not that of Leland Stanford, but rather that of his son: Leland Stanford Junior University.

The university opened its doors in 1891. Herbert Hoover, who was later elected president of the United States, was part of the first class. But don’t let this fact suggest that Stanford was a prestigious university back then. Hoover came from a modest background and only picked Stanford because he had grown up in Oregon and was interested in engineering, which the university was trying to specialize in. Indeed, for most of the 20th century, Stanford University remained a rather provincial university.

3/ Then Stanford became the beating heart of Silicon Valley thanks to Fred Terman.

Specifically Terman had two things that he combined and in doing so radically transformed Stanford:

A taste for encouraging entrepreneurship among his students. This was illustrated by his supporting two of them, Bill Hewlett and David Packard, in forming a company. They both had graduated from Stanford in electrical engineering in 1935 and went on to found their eponymous company in a garage. The rest is HP history, but it’s a case that is very much representative of Terman’s mindset when it came to what he told students they should do with the knowledge acquired at Stanford: founding their own company was a perfectly valid option.

An acute sense of how to attract money from the US government. Terman wasn’t necessarily interested in the outcome; what he wanted was his beloved university to have its share of the pie that Washington, DC was allocating to universities across the country in order to enroll them in the war effort. The first opportunity was World War II, and, to be frank, Stanford wasn’t ready: Terman himself, although he was a pillar of Stanford’s electrical engineering department, had to move back East to work with his peers at a secret laboratory on the Harvard campus.

But after WWII, Terman declined the compelling offers made by East Coast universities and decided to go back West to provincial Stanford—and to help it catch up in the race by grabbing taxpayer money. He saw that the entrepreneurial tradition he had been supporting at Stanford could be turned into an asset, rather than a liability, in this particular race. And what made Terman such a great ecosystem builder was that he combined his taste for encouraging entrepreneurship with his acute sense of attracting money from the government. This proved a winning combination—one that gave birth to Silicon Valley.

4/ I already wrote about what happened during and right after WWII in my essay A Brief History of the World (of Venture Capital), published in 2016:

When the Japanese attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor, it was a wake-up call. Suddenly, the US found itself at war with Japan in the Pacific and Germany in Europe. Both Axis nations were powered by impressive scientific and technological capabilities. Germany, notably, had a superior academic apparatus, with all those Nobel Prizes in physics and chemistry, that helped its army deploy advanced radar technologies designed to help bring down US bombers — to the point where the probability of an American bomber pilot surviving the war in Europe was no higher than 25%.

This challenge was tackled by the Roosevelt administration with the help of a renowned engineering scholar named Vannevar Bush, who went on to chair the newly formed Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD).

The problem that Bush was trying to solve was that the military needed top-notch researchers, but the best researchers preferred to join academia than enroll in the military. As a result, only a few scientists accepted being placed in charge of in-house military research, and those that did were clearly not the best. Bush, who previously worked in the MIT Department of Electrical Engineering, persuaded President Roosevelt to give up on enrolling researchers in the military in favor of allocating public funds to the best universities in the country. Instead of recruiting researchers and forcing them to renounce their academic careers in the process, why not leave them where they are and provide them with the resources necessary to conduct their research on matters that were of interest to the US military?

A lot of money was subsequently poured into elite universities, all of them located on the East Coast. At Harvard University and MIT in Cambridge, and at Columbia University in New York City, secret research laboratories were inundated with public money and crowded with the best scientists in the country, all with one mission: to invent the new, cutting-edge technologies that would help the US regain the upper hand. Among those secret laboratories was the Radio Research Laboratory at Harvard University (where research aimed at finding ways to block enemy radar), whose head was Frederick Terman, a member of Stanford University’s engineering faculty and one of Vannevar Bush’s former MIT students.

After the end of World War II, again following Vannevar Bush’s recommendations, a massive amount of public spending was once again allocated to continuing the research effort. The war, after all, wasn’t really over: there was the Korean war, then the Cold War. The G.I. Bill, designed to encourage veterans to attend university so as to facilitate their return and help them find jobs, matched the effort on the research front with a massive upheaval of the country’s higher education system. Both efforts, in research and in higher education, contributed to turning the US academic system into a powerful growth-generating machine, which in turn triggered the post-war boom.

5/ Terman built Stanford as an entrepreneurial ecosystem because he managed to seize this extraordinary opportunity (the government pouring an infinite amount of money into high-tech research within universities).

Here’s how I described the whole system in the same 2016 article:

Frederick Terman, who headed the Harvard Radio Research Laboratory during the war, was back on the West Coast as the provost of Stanford University, which he intended to turn into a leading university in the sciences. To achieve that goal, Terman made it a priority to attract the formidable budgets that, following Vannevar Bush’s guidance, the Department of Defense now allocated to advanced research in US universities.

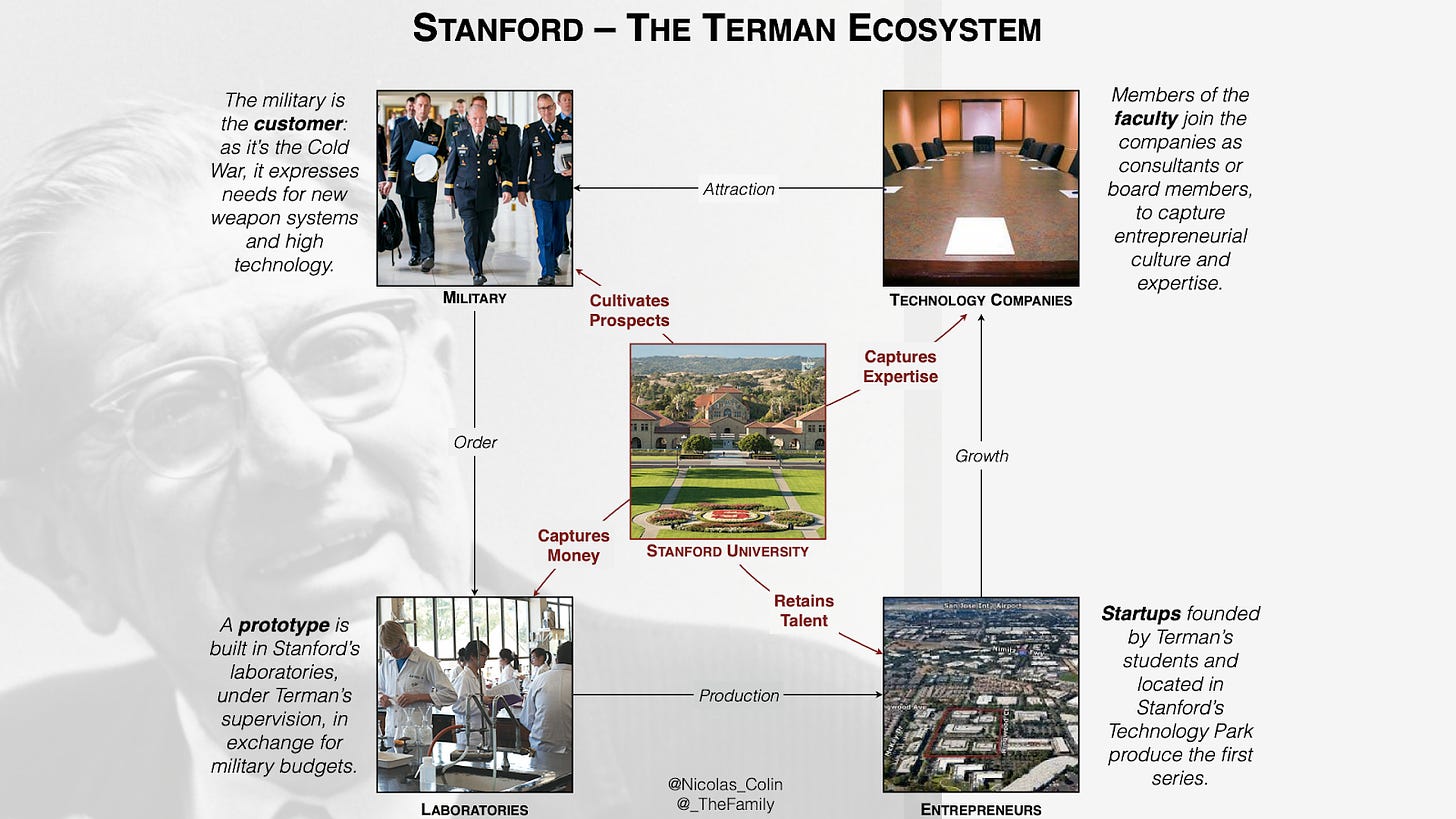

And so it was military procurement, both by the government and weapons manufacturers, that enabled the founding of the first entrepreneurial ventures in what was to become Silicon Valley. The sophisticated system that Terman put in place at Stanford relied on four pillars:

First, reach out to military prospective customers to better understand their needs, then offer to craft them a prototype in Stanford’s research laboratories—this generated substantial revenue for the university and strengthened its trusted relationship with key military figures;

Second, if the prototype satisfies the customer, encourage one of your students to found a company and manufacture the product at a larger scale—this inspired an entrepreneurial spirit among the students and contributed to stimulating their hard work in the university’s laboratories;

Third, make sure a member of the Stanford faculty (if not Terman himself) becomes a board member or consults with that newly founded company—this contributed to training Stanford scholars in business and turned them into better teachers and researchers;

Fourth, provide office space in the Stanford Research Park, which was made possible by the fact that the university was the primary landowner in Palo Alto—this ensured that the upstart company stayed close and helped the nascent entrepreneurial ecosystem reach a higher density.

Those strong links, established within a very tight and dense ecosystem, had extraordinary consequences on Stanford:

First, it turned it into a financial focal point. Stanford University became the preferred contractor at the prototyping stage, which made Frederick Terman inescapable when it came to gaining access to military budgets: if you wanted to attract defense money for your scientific work, you had to go through Terman.

Second, as a result this nascent Stanford ecosystem attracted more promising students, military customers, talented engineers and, later, private investors.

Third, it gave rise to a new approach in academic research, driven by the customers’ demands rather than being pushed by laboratories or the agendas of national research agencies. Steve Blank goes as far as to refer to Frederick Terman as the first advocate for the customer development method: while Stanford converted to a customer-driven, entrepreneurial culture, other universities such as Berkeley continued their“focus on Big Science and National Lab.” This is what ultimately made Stanford University and Silicon Valley such a magnet for venture capitalists.

6/ The whole system included many feedback loops around the original startup community that was Stanford University and the Stanford Research Park.

Terman effectively built the five institutions that, to me, make a healthy entrepreneurial ecosystem (see my essay on the topic here, or the shorter version here on the Techstars blog):

Was entrepreneurship highly regarded? Yes, because again, Terman had a taste for students who wanted to build their own venture in a garage. Unlike other faculty members, he was as supportive as you could get whenever one of his students wanted to pursue that path.

Did entrepreneurs work hard? Yes, they did, because in Terman’s approach company formation only happened when a first order by a large customer was already on the way. Hence entrepreneurs really needed to work hard to fulfil that customer’s expectations.

Were there resources to cover higher risks during the growth phase? That was one of the goals of locating the whole effort on the Stanford campus: money was provided by customers in the defense industry, but Stanford provided real estate, advice, and talent.

Was talent moving around instead of being locked up? Yes, for two reasons: It was California, a state that is well known for not enforcing non-compete clauses. And then, because the whole ecosystem was nested in the university, it emulated the cooperative spirit of the academic world.

Did newcomers prefer to found startups rather than join an existing firm? Yes, to a great extent: after all, didn’t entrepreneurs such as William Shockey settle in Palo Alto precisely to benefit from Terman’s incredibly supportive ecosystem?

7/ Many people misunderstand the role that Stanford has played in the history of Silicon Valley.

They think a university is merely a pool from which entrepreneurs can tap into top high-tech talent. But Terman contributed much more than talent:

Again, as pointed out by Steve Blank, Frederick Terman inspired the entire Stanford startup community with an obsession for building what customers want (echoing Paul Graham’s famous words). This is why, as stated by this great article in Scientific American, to this day “Silicon Valley is [still] dominated by what we call the “need seekers,” companies that focus on discerning their users’ actual needs, both spoken and unspoken; figuring out how to meet those needs; and then getting the necessary product or service to market as fast as possible.”

And Terman designed and operated a self-sustaining system, with a flywheel turning so fast and churning out successful tech companies at such a high rate that it became a perpetual entrepreneurial machine, supporting the rise of many generations of highly successful tech companies—from Fairchild Semiconductor in the late 1950s to Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore’s Intel in the 1970s, Apple and Atari in the 1980s, Netscape in the 1990s, Google in the early 2000s, and then the likes of Facebook, Airbnb and Uber.

I once designed a graphic to explain it all. Here it is:

8/ We can draw three lessons from the legacy of Frederick Terman.

The first is rather negative: As Brad and Ian righly state in their book, there isn’t one single recipe that works for building an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Terman’s experiment worked extraordinarily well because it was California, because it was the Cold War, and because it was Terman. Anyone who tries to apply the very same recipe without acknowledging the importance of contextual rationality is in for a rude awakening: it likely won’t work.

In fact, Terman himself, after he retired as engineering dean of Stanford University, became a consultant and started touring the world to help other regions build their own Silicon Valleys. But it didn’t work. Here’s what my friend Vivek Wadhwa of Carnegie-Mellon University wrote about that back in 2013:

Stanford University, which is at the heart of Silicon Valley, had given birth to leading companies such as Hewlett-Packard, Varian Associates, Watkins-Johnson, and Applied Technologies. These companies were pushing the frontiers of technology. There was clearly something unusual happening here—in innovation and entrepreneurship.

Soon enough, other regions were trying to copy the magic. The first serious attempt to re-create Silicon Valley was conceived by a consortium of high-tech companies in New Jersey in the mid-1960s. They recruited Frederick Terman, who was retiring from Stanford after having served as provost, professor, and engineering dean.

Terman, sometimes called the “father of Silicon Valley,” had turned Stanford’s fledgling engineering school into an innovation engine. By encouraging science and engineering departments to work together, linking them to local firms, and focusing research on the needs of industry, he created a culture of cooperation and information exchange that has since defined the region.

That was the mixture that New Jersey wanted to replicate. It was already a leading high-tech center—home to the laboratories of 725 companies, including RCA, Merck, and the inventor of the transistor, Bell Labs. Its science and engineering workforce numbered 50,000. But because there was no prestigious engineering university in the area, its companies had to recruit from outside, and they feared losing their talent and their best technologies to other regions. (Even though Princeton University was nearby, its faculty generally shunned applied research and anything that smelled of industry.)

New Jersey’s business and government leaders, led by Bell Labs, decided that the solution was to build a university much like Stanford. And that is what they hoped Terman would do.

Terman drafted a plan, but he could not get it off the ground, largely because industry would not collaborate. This history was documented by Stuart W. Leslie and Robert H. Kargon in a 1996 paper titled “Selling Silicon Valley.” They tell of how RCA would not sign up for a partnership with Bell Labs, how Esso didn’t want to share its best researchers with a university, and how Merck and other drug firms wanted to keep their research dollars in house. Despite common needs, companies would not work with competitors.

Terman would later try again in Dallas. But he failed for similar reasons. [All in all], the magic never happened—anywhere. Hundreds of regions all over the world collectively spent tens of billions of dollars trying to build their versions of Silicon Valley. I don’t know of a single success.

What Terman failed to recognize is that it wasn’t academia, industry, or even the U.S. government’s funding for military research into aerospace and electronics that had created Silicon Valley: it was the people and the relationships that Terman had so carefully fostered among Stanford faculty and industry leaders.

9/ The other lesson, as mentioned above, is one of contextual rationality.

It’s not because you needed a university as the base for a thriving startup community in the 1950s that a university is still needed today. I see the fascination of almost every ecosystem builder in the world with having a university somewhere in the neighborhood. Even Paul Graham, a pure byproduct of Silicon Valley in the 2000s, has written at length about the importance of having the equivalent of Stanford:

What nerds like is other nerds. Smart people will go wherever other smart people are. And in particular, to great universities. In theory there could be other ways to attract them, but so far universities seem to be indispensable. Within the US, there are no technology hubs without first-rate universities-- or at least, first-rate computer science departments.

So if you want to make a silicon valley, you not only need a university, but one of the top handful in the world. It has to be good enough to act as a magnet, drawing the best people from thousands of miles away. And that means it has to stand up to existing magnets like MIT and Stanford.

However, I think this fascination with universities such as Stanford is misplaced. Back then, a university made all the difference because of two things:

You needed the enthusiastic support of your beloved university professor (Terman) to tilt the scales in favor of the odd option of founding your own company. That’s clearly not the case anymore: everyone wants to be an entrepreneur these days!

It was still a world before the technological revolution leading to the current age of computing and networks, and so founding a ‘tech startup’ required a lot of high-tech research and development, which could only be done in a university laboratory.

But that’s not the case anymore, as I wrote in an article published two years ago in Forbes:

Beyond that, there are many misunderstandings regarding the place of universities and public research laboratories in the daily practice of innovation. After the Second World War, only public entities held the intellectual resources and the equipment necessary to conduct cutting-edge scientific work—and those were at the heart of that era’s innovation process. But today, the context has changed. The resources needed to innovate are much better distributed, and so innovation has become more ubiquitous. As a result, universities are largely absent from the great waves of innovation of recent years, which are increasingly driven by large tech companies (Google’s self-driving cars, Amazon’s voice assistant) and developer communities (as in the cases of mass computation and cryptocurrencies, among others).

10/ Finally, Frederick Terman reveals the misalignment between a public policy’s goal and what it actually delivers.

Many universities in the US drank from the same well as Terman’s Stanford University. But only Stanford turned into the base for a successful startup community. The reason is that Terman wasn’t encumbered by the goals of the Department of Defense that allocated all that money. He was interested only (mostly) in the money, and he was ready to redesign its entire engineering department to secure a big chunk of it. As I wrote in The Problem With Taxpayer Money in Startups (December 2019):

This is one way to look at the story of Silicon Valley. It was not planned by the government. Rather it was born out of the efforts of Frederick Terman, then the Provost at Stanford, to access the government’s money in the context of waging the Cold War.

Terman had a very precise (and selfish) idea of what he wanted to do with that money: grow his beloved university and turn it into a vibrant ecosystem for research and entrepreneurship. He didn’t care that much about the Cold War. But he was ready to do what it took to grab as large a slice of that money as possible.

Later, the US government put in place financing schemes, such as the Small Business Investment Company (SBIC), that were less than perfect. But upstart entrepreneurs and investors, junkies that they are, were willing to use them because they allowed them to access scarce resources, cut their teeth, and accumulate experience. Most of the first-generation VCs in Silicon Valley, like Franklin “Pitch” Johnson, used the ill-designed SBIC at the beginning before eventually moving away from it. For the state, though, it was mission-accomplished: it had applied pressure by providing a direction, enabling many people to get into the game by making it relatively easy to hack resources such as the SBIC program, however ill-designed they may have been.

And so that’s my conclusion.

More than a Stanford faculty member, Terman was a hacker—a hacker of American taxpayer money. He didn’t really care about what the US government was trying to achieve. But he had a taste for entrepreneurship and for supporting entrepreneurship, combined with a sense of how to attract government money. Terman hacking his way into the procurement maze of the Department of Defense gave us Silicon Valley, the cradle of the current great surge of development. Will others, in other places in the world, learn from his playbook and turn into hackers themselves?

If you’re interested in ecosystem building, check out my review of Brad Feld and Ian Hathaway’s new book, The Startup Community Way: Anyone Can Build an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. And then, whether you read Brad and Ian’s book or not, let me know what you think!

From Paris, France 🇫🇷

Nicolas