Hi, it’s Nicolas from The Family. Today, I’m pursuing the discussion on the ‘Great Fragmentation’ and discussing its consequences from an investor’s perspective.

The argument I made in a recent Sifted column is that the world is fragmenting at a fast pace and that European founders (and the investors who back them) should focus more on their domestic market as a result. It generated quite a lot of pushback:

In his newsletter Sunday CET, Dragos Novac offers a nuanced discussion of fragmentation and its consequences for startups. Read the whole thing, but there were two arguments I’d highlight. First, according to Dragos, politics doesn’t interfere with startups [actually “Tech is decoupled and politics is outta control”]: I disagree, but I figure this is a common assumption in the tech world. The other idea is that there’s now a global infrastructure for scaling tech businesses up across borders—and with that I agree.

Then there was a subsequent discussion on Twitter with Hussein Kanji of Hoxton Ventures. It’s not the first time Hussein and I have had this argument. For him, expanding in either the US or China is a necessary step for hitting a home run in the tech world. I agree this is the optimal gameplay, yet it’s becoming more difficult and will lead many people, whether founders or investors, to miss out on the opportunities brought about by the ‘Great Fragmentation’ 👇

1/ The whole discussion reminded me of Pankaj Ghemawat’s work on “Actually, the world isn’t flat”. I first heard Pankaj explain his thesis at a conference at UNESCO in Paris, sometime around 2012. Here’s the quick version (actually, a TED talk) of what he said that day 👇

In short, there’s a discrepancy between the widespread assumption that we live in a globalized world and the actual situation as revealed by data.

2/ There are three reasons for this disconnect that Pankaj calls “globaloney” 😅

The first is the “real dearth of data in the debate”. When you ask people for data that supposedly reveal how the economy has globalized, they come up with fantasy figures that are way off the mark when compared with reality. This is true, for instance, for phone calls (almost all of them are local rather than cross-border); the percentage of first-generation immigrants in the world (no more than 3%); foreign direct investment (less than 10% of the total); the export-to-GDP ratio (less than 20%); even social connections through online platforms (indeed, almost all of them are local—I actually quit Facebook because I felt trapped within a franco-français network).

Even more interesting are the two other reasons for “globaloney”, because they both impregnate the startup world. One is “peer pressure”. We tech people have all heard that “startups must be global from Day One”, and it’s rare to hear someone argue that they should focus on their domestic market. Yet there are many, many examples of companies that have turned into smashing entrepreneurial successes while remaining focused on a local or continental market. But we don’t talk much about those startups, a group that Byrne Hobart recently called the “Software Mittelstand”—quite simply, they’re not going to be featured in TechCrunch.

The other reason has to do with what Pankaj calls “techno-trances”. In his talk, he mentions

Exaggerated conceptions of how technology is going to overpower in the very immediate run all cultural barriers, all political barriers, all geographic barriers.

Again, for those of us in the tech world, that rings true (and perhaps hits a bit close to home for some 😉).

3/ Now why do we all have this enduring impression that tech companies can be nothing but global? Here are some reasons:

The high fixed costs that characterize tech companies, and the related increasing returns to scale, mean that these companies need a large market to generate returns on invested capital. This is true in every capital-intensive industry, including manufacturing, but even more so in tech, where the scalability curve can be so steep.

Many successful tech companies in the Internet era operate a business that’s essentially intangible. This was true for Netscape and Yahoo. It’s true for Google and Microsoft, as well as for social media, PayPal, Stripe, Netflix, and Spotify. It’s relatively easy to be global when you’re in an intangible business!

As for those companies with more of a tangible footprint (Amazon, Alibaba, Uber), they were launched on a domestic market so large (either the US or China) that their resulting size makes them appear to be global. Even if theirs is a tangible business, their brand is known globally and in some fashion they’re present on every continent.

4/ But echoing Pankaj’s conference, I can’t help but feel a huge gap between the impression of all those companies being global and the reality. I’ve been travelling a lot over the past two years, expecting to be able to use the same apps everywhere. Yet that was absolutely not the case:

Ride sharing is a case in point. My first trip to Mainland China, in 2017, was after Didi had acquired Uber’s operation there (2016). And so to move around Shanghai I had to download the Didi app (which has an English version, fortunately). The same happened in many other places: in Israel, I had to download Gett (Uber is there, if I remember correctly, but not many drivers use it); in Barcelona, where Uber is illegal, you need Cabify; and in Singapore, you can’t get around without Grab.

The same is true in many other sectors. Obviously Mainland China is an outlier because the Great Firewall makes it close to impossible to use services we take for granted in the West, like Google and Facebook. But I actually started to use WhatsApp in Singapore because they told me people were not keen to communicate via email there. And as for retail, I was very surprised to discover that Amazon isn’t present in Israel (which, as an aside, made it difficult for readers there to buy my book Hedge 😉).

So you may see a global world—until you actually start criss-crossing it and realize that very few applications are actually used at a global level!

5/ Now, don’t get me wrong: there is such a thing as the global business world. It’s found in a bundle of premium services that include airport lounges, airlines, four- and five-star hotels, American Express, limo services, global consumer brands (mostly fashion and luxury goods), and various concierge services. I can vouch for all those actually having a global imprint, and they clearly give any business traveller the impression that the world is flat indeed—and that everyone in it speaks English 🇬🇧

But I don’t find that this kind of globalization translates into the tech world. People working in tech investment are (rightfully) wired for thinking globally because they’re on the hunt for the most scalable companies that can expand on the largest addressable markets. But like all members of the global business world (myself included), they’re bound to misinterpret technology:

The large part of the global elite is skeptical toward tech-driven products. Having access to the bundle of services found in the global business world (and only found there), they don’t see the point of relying on cheap, convenient services such as Uber or Airbnb. Why bother to download the Uber app when your PA can order a limo that will wait for you at the airport?

The rest of the business elite (arguably the minority) falls victim to a different kind of excess: they’re exceedingly confident in the ability of technology to erase borders. This mix of “peer pressure” and “techno-trances”, to borrow Pankaj’s words again, is what makes it so difficult to have a conversation about the ‘Great Fragmentation’ in the tech world—until you realize Uber is not available everywhere.

Both parts of that elite are wrong, albeit in different manners. The former underestimates the ability of tech startups to change the world; the latter wrongly assumes that tech startups are programmed to ignore borders and that tech and politics are disconnected.

6/ It’s easy to spot that these assumptions are false if you realize that consumer markets are driving the growth of tech companies—whether directly or indirectly:

A member of the backward-looking elite is fundamentally out of touch with what consumers are consuming on a daily basis. They have access to premium services and their market sensitivity comes only from what they read in the papers. Not every wealthy investor has the discipline of Warren Buffett driving to a McDonald’s every morning to buy breakfast.

As for the forward-looking elites (including us the tech elite), we’re still part of the elite and are thus immersed in this global business world. It makes us forget how fragmented the world is from the perspective of most people—who speak different languages, were brought up in different cultures, and have different habits when it comes to consumption.

In short: Google and Facebook give the impression of globality because theirs are such formidable brands, and billions of people use their products every day. But we shouldn't be mistaken: Marriott, Hilton and Amex, although they have smaller market caps, are more globalized than Google or Facebook will ever be. To paraphrase Seth Godin, a tech business is rarely more global than the users it is able to attract. Some startups focus on their domestic market because that is where most of their users are.

7/ I think we lack a framework to reflect on a more fragmented world and the many opportunities that it still provides to invest in tech companies. Like all human beings, those working in tech base their assumptions regarding the future on what they’ve experienced in the past. It’s true that the past years highlighted a global digital economy. But now that we’re going through the next stages of the current “great surge of development” (Carlota Perez’s words), we have to acknowledge that the world is indeed fragmented and that it’s going to become even more so in the future.

And so I’d like to introduce three leads that we need to follow in order to come up with that framework for sounder investment decisions in a fragmented world. I think that three ideas/trends should be borne in mind by all those working in tech investment with an interest in Europe:

Returns. The more tech companies enter regulated markets and/or tangible industries, the more difficult it will be for them to generate returns. Investors need to realize that there’s a difference in terms of return profile between advertising, retail, financial services, and real estate.

Divergence. As I mentioned in the introduction, it’s true that a global infrastructure made of, say, Stripe, Slack, AWS, and Facebook, makes it easier to start tech companies. But paradoxically it will also give birth to tech companies that are more local, not more global.

Dynamics. The more some tech companies (Byrne’s “Mittelstand”) succeed on local or regional markets, the more they’ll attract additional capital, thus boosting productivity, expanding the addressable (local) market, and increasing the potential returns for the next generation.

8/ Let’s start with what becomes of return on invested capital in a world eaten by software. This is a topic I’ve already written about (the framework of the Northern Side and the Southern Side, which is especially useful when it comes to capital allocation) and on which I intend to expand soon. You should subscribe to the paid version of European Straits if you want to be in the loop 👇

Here, let me share two ideas:

The process of software eating the world means startups are being launched in industries where it’s ever more difficult to generate increasing returns to scale. The history of business in the 20th century is about every industry embracing the paradigm of mass production, one after the other—from the car industry early on to the luxury industry sometime in the 1980s (btw, I’m working on an “11 Notes on LVMH” to dig into that). But there’s a reason why some industries embrace the new paradigm later than others: it’s more difficult in some areas to deliver high returns. We have to get used to this very important idea: the more progress we make in software eating the world, the lower the returns. Quite simply, software doesn’t perform the same magic in industries that are more tangible and on markets that are more regulated.

As for Europe, think about oil fracking in the US. Fracking is a sector that has been booming over the past 15 years, to the point of the US becoming self-sufficient when it comes to energy production. Yet, as frackers have painfully realized over the past two months, theirs is a business that’s sustainable only if global energy prices are high enough to make it profitable on a marginal basis—which hasn’t been the case since the Saudi-Russian war on oil prices has brought the market to a near collapse. Yet that’s the exception rather than the norm. And so, here’s my point: European startups are to US tech giants what US frackers are to Saudi Aramco. In theory, it doesn’t make sense to bet on fracking if you consider Aramco’s ability to scale up production. But in practice, prices are bound to go up and down, in which case diversification is the rule.

In short: software eating the world is correlated with a lower return on invested capital; at some point in that process, betting on European startups with lower returns (because of smaller markets) will become attractive from an investment point of view; sure, tech companies thriving on larger markets (US and China) will always look more attractive over the short term; but aren’t investors supposed to diversify?

9/ Then there’s the idea of divergence. I 100% agree with Dragos Novac 👆 that we now have a global infrastructure made of cloud computing platforms (AWS), payment infrastructures (Stripe), and investors with a (rather) global foothold (Index Ventures). On paper, that should make it easier for any tech startup to aim higher when it comes to market size and doing cross-border business.

But what this global business infrastructure delivers for founders with a global ambition also exists for those who care more about entering a difficult industry (think: healthcare, financial services, education, real estate) rather than expanding on a global market (music, advertising, media).

And so as the pace of technological (and financial) progress increases, we’re bound to witness the divergence between two very different categories of ambitious founders:

Some will aim at building global empires and will embrace industries that lend themselves to such a strategy—that is, anything that’s intangible and not too regulated (because regulation is always synonymous with cross-border frictions).

Others will tackle local challenges and use this unprecedented ability to scale to increase their velocity at an early stage, raise more capital, and use it to penetrate local markets that are complicated due to the width of the moats that protect them.

I’m talking about a systemic phenomenon here: if you provide additional capabilities to founders, you end up with responses that are divergent. Some will use these capabilities to expand on a larger scale; others will use them to deepen their penetration of a difficult local market—eventually generating returns through economies of scope (a broader value proposition) rather than economies of scale.

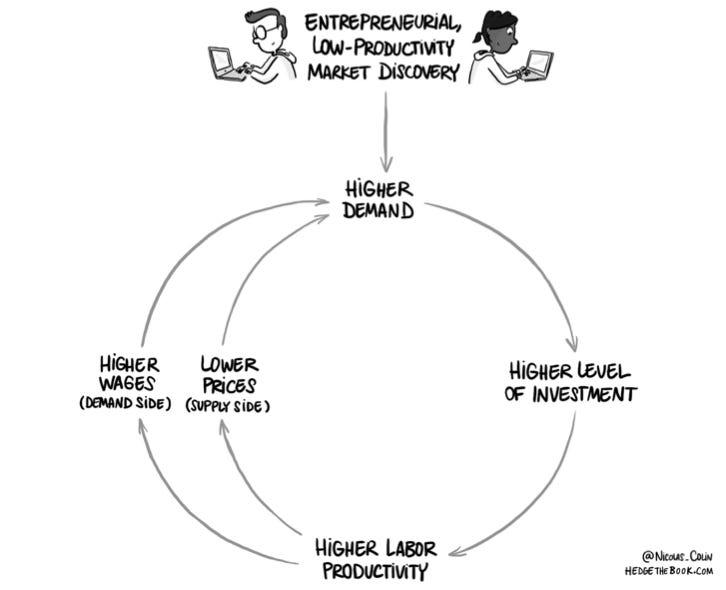

10/ Finally, I expect investors—especially those in venture capital—to have the ability to think about market dynamics. Let me share the following illustration from my book Hedge (inspired by the work of economist James Bessen):

Like in this illustration, this is how I expect things to play out in Europe:

Some entrepreneurs will spot an opportunity to innovate on markets that are essentially fragmented (be it due to language barriers, cultural barriers, or regulatory barriers).

At first, returns will be low, but early, unexpected successes will attract more investment, which in turn will contribute to increased productivity.

The resulting economic surplus will be reinvested in the form of lower prices (which means more customers) and higher wages (which means more workers).

Then at some point, even at a local (or continental) scale, you can reach critical mass and generate the returns that make it sustainable for venture capitalists to back you.

In conclusion, 10 sections is a lot, but it’s not enough to reach a definitive conclusion on such a tricky subject—the conditions of success for those building startups in Europe. This is a discussion that I intend to pursue in the paid editions of this newsletter, and you should subscribe if you want to participate 👇

⚠️ Last week, Willy Braun (of Gaia Capital Partners), Vincent Touati-Tomas (of Northzone) and I launched Capital Call, a weekly newsletter curating what European tech investors are thinking—in their own words. The whole thing is explained here—go read it, and then subscribe! 👉 About Capital Call.

🇪🇺 About that, Gonz Sanchez, publisher of Seedtable, is emerging as a major player in the European tech ecosystem. I was honored to be a guest of the podcast he just launched as part of Seedtable. Follow this link to listen 👇🎙

🤓 Apart from Pankaj Ghemawat, from whom I’ll share various works related to today’s topic in Friday’s (paid) edition, there are many people who have inspired my thinking on the ‘Great Fragmentation’.

James Crabtree, a former correspondent of The Financial Times in Mumbai, is the author of the Billionaire Raj, a book about India’s Gilded Age, and an astute observer of the global economy fragmenting, viewed from an Asian perspective.

Rana Foroohar, also with The Financial Times, has been writing for years about tech companies, their obsession with scaling up, and the barriers that some of them have encountered in doing so. Her views on deglobalization are a must-read if you want to make sense of today’s world.

Janan Ganesh (I must admit—he also writes in The Financial Times 😅) is a spirited columnist with a knack for depicting global politics and business with exactly the right amount of relevance and irony. One of his pieces is on today’s topic, and I’m glad to share it with my subscribers.

Dani Rodrik is NOT with The Financial Times, but is rather a professor at Harvard University. Quite simply, he is the best economist to understand the political economy of trade in a world that has been going from global to fragmented over the course of 20 years. A must-read.

👉🏻 To discover their articles and many others related to today’s edition, become a paying subscriber! The package will be sent to subscribers only with the forthcoming Friday Reads edition 🤗

In case you missed it:

Launching My Executive Sparring Practice—for everyone.

Think You Understand Capitalism? Think Again.—for everyone.

The Entrepreneurial Investor: An Overview (Round 1)—for subscribers only.

China Drifting Away?—for subscribers only.

The Rise of a New China—for everyone.

Law Firms, Disunited Europe, Venture Capital—for subscribers only.

European Startups as an Asset Class—for everyone.

Will Fragmentation Doom Europe to Another Lost Decade?—for everyone.

From Normandy, France 🇫🇷

Nicolas