Vaughn Tan on Uncertainty

Today: Vaughn, author of “The Uncertainty Mindset”, spent an hour with founders in The Family’s current batch of startups.

The Agenda 👇

Strategy and innovation

Risk and uncertainty

Learning while you build

Innovation as a means rather than an end

Thumbs up/down for last week

Vaughn Tan, author of the landmark book The Uncertainty Mindset, is one of the most inspiring authors these days in the field of business strategy.

I admit I can’t exactly remember how I discovered Vaughn (but to whomever wrote that tweet: thank you ❤️). But my wife Laetitia and I instantly were carried away by his work at the crossroads of strategy (a topic I love), uncertainty (a concept that Laetitia has been appropriating in her own work), and food (because, well, that’s really important to both of us 😋)—not even mentioning the fact that Vaughn comes from Singapore 🇸🇬, which is such a fascinating place!

So when my colleagues at The Family asked me to organize a series of talks for founders on our current batch with a focus on business strategy, I immediately thought about having Vaughn as a guest speaker. I’m very grateful that he immediately agreed, and I really enjoyed our 1-hour conversation last Friday, of which I wanted to give you a glimpse in this edition.

How Vaughn got interested in strategy

Before becoming a strategist, Vaughn worked for a few years for Google. Because his training was as a behavioral sociologist, he got interested in the growing pains that Google was experiencing at the time and asked himself the following question: why do organizations become so bad (more boring, less innovative) as they grow? He embarked on an academic journey to try and solve that mystery, eventually writing a PhD thesis at Harvard before going on to teach at UCL in London and writing The Uncertainty Mindset after years of research in the kitchens of the most innovative restaurants in the world.

By the way, what Vaughn shared about Google reminded me of this essay by another former Googler, Steve Yegge: Google doesn't necessarily need innovation.

The definition of strategy

Vaughn defines strategy as“taking action with the desire to achieve a particular outcome”.

That can be confronted with the definition offered two weeks ago by another guest, Ben Robinson: “The quest for scale”—which in turn echoes what Vaughn said about the specific case of tech startups. In that field, which is characterized by “massive scalability”, strategy is all about finding “the correct point of entry to apply leverage and deliver on that scalability”.

And while we’re defining strategy, Jorge Juan Fernández, a regular reader of this newsletter, recently shared various definitions of strategy he’s been compiling over the years. Here are a few of them:

“The set of integrated choices that define how you will achieve superior performance in the face of competition.” (Michael Porter)

“A route to continuing power in significant markets.” (Hamilton Helmer)

“Strategy is not the consequence of planning, but the opposite: its starting point.” (Henry Mintzberg)

“The process of going from an existing condition to a preferred one.” (Milton Glaser)

“An integrated set of hard-to-reverse choices, made ahead of time in the face of uncertainty, to create and capture economic surplus.” (McKinsey Academy)

“Strategy, with a capital S, is a plan to achieve the goal.” (Eli Schragenheim)

“A business strategy is a set of guiding principles that, when communicated and adopted in the organization, generates a desired pattern of decision making.” (Michael Watkins)

“A good strategy is a set of actions that is credible, coherent and focused on overcoming the biggest hurdle(s) in achieving a particular objective.” (Richard Rummelt)

“Strategy is the thinking that drives all my actions in pursuit of success.” (Robert Burgelman)

“How to make choices in order to control events rather than allowing events to control your choices.” (Victor Cheng)

“The smallest set of choices to optimally guide the other choices.” (Eric Van den Steen)

The relationship between strategy and innovation

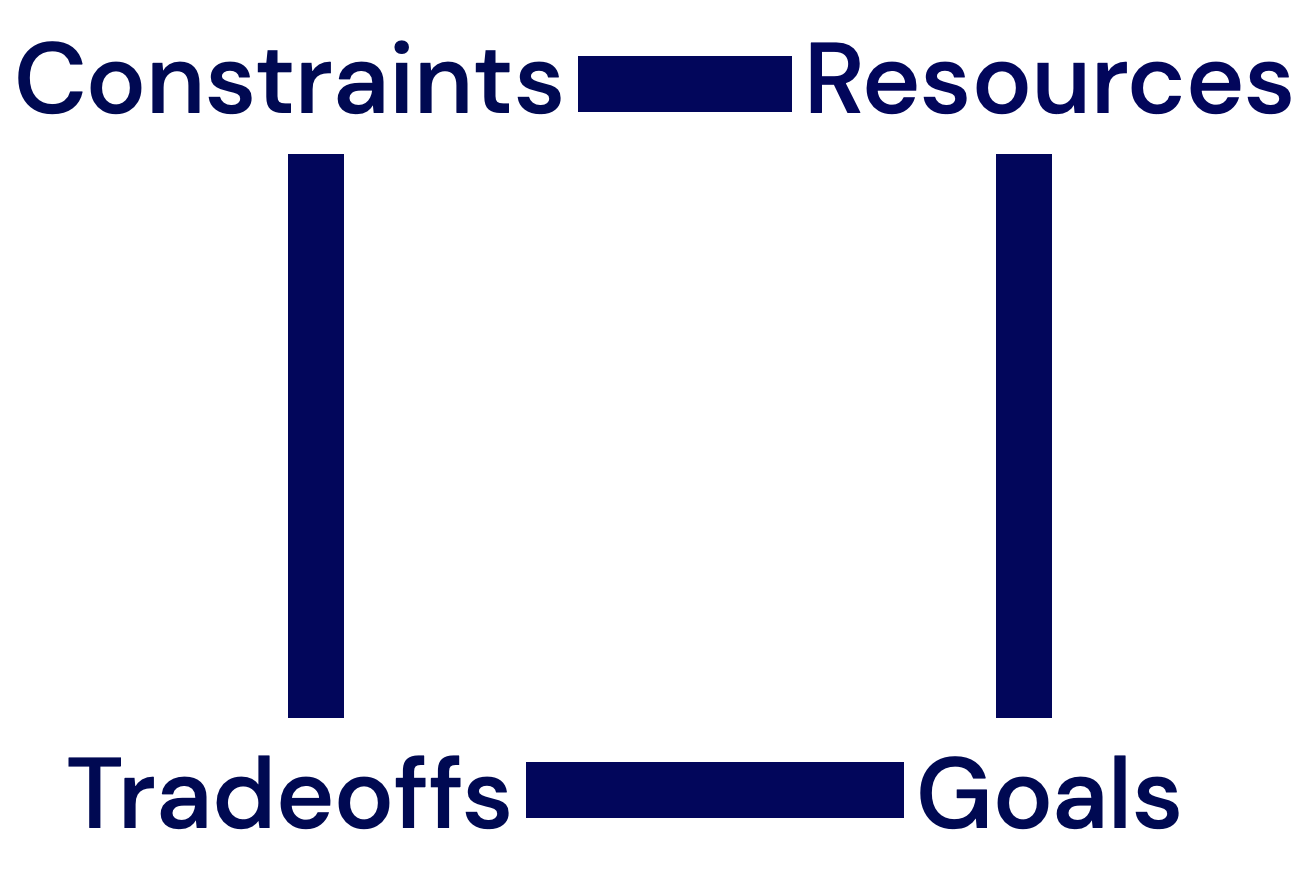

I asked Vaughn about this idea, discovered via Michael Raynor, that innovation is all about breaking constraints while strategy is about embracing them. In response, Vaughn suggested this image of a square that sets the stage for doing strategy:

In many cases, deciding on a strategy within that square requires implementing innovation—as in, due to certain constraints, resources, and tradeoffs, there are certain goals that can only be achieved through innovation.

However Vaughn warned us against confusing innovation with creativity. Creativity leads to building new things, but innovation is about “new things that are useful to someone”.

I remember that a long time ago I often used Scott D. Anthony’s definition of innovation, which is very much in line with that: “Doing something differently with an impact”.

On this topic, you can go further with these essays from a few years ago:

Startups Are Not About Innovation (The Family, April 2017)

Startups: It's NOT About R&D (European Straits, November 2017)

The difference between risk and uncertainty

The next part of our discussion was about uncertainty and why it matters. Readers of this newsletter are likely familiar with the fact that uncertainty differs from risk, as explained in All About Risk and Uncertainty (December 2020):

Everyone in the tech world is interested in risk because building a startup or funding it is supposedly about taking risks. A concept that’s less well understood, however, is that of uncertainty—which, it turns out, might be even more relevant to understanding what is happening in the tech world these days.

Vaughn shared a more detailed framework. Quoting an issue of his own newsletter:

Only use “risk” as a label for situations where the actual future outcome is unknown but all possible outcomes and their respective probabilities are known (instead of using “risk” to indiscriminately label all situations where future outcomes are unknown).

For founders and executives, this is the key: never delude yourself with the idea that you’re confronted with risk when in fact you’re confronted with uncertainty—because these two things call for a very different approach from a strategic perspective (more on that below).

In this part of the conversation, Vaughn also introduced the rarely used word “totipotency” (like many words in the field of complexity theory, it’s been inspired by biology):

The ability of a cell, such as an egg, to give rise to unlike cells and to develop into or generate a new organism or part.

Has the world become more uncertain?

Then I asked Vaughn if he thought the world had indeed become more uncertain, or if we’re just learning to recognize that what we previously thought of as ‘risk’ is in fact ‘uncertainty’. It’s true that we have matured in our understanding of these things and that we’re becoming more accurate in using these two categories; but there are also certain trends that indeed make the world more uncertain:

Units that were previously separated are now more connected. Think about how countries had long lived in relative autarky vs. how connected they are today, as illustrated by COVID-19 and its variants spreading across borders at a very fast rate.

These units, or modules, are themselves becoming more complex on the inside, thus fostering totipotency. (Remember, as I explained in Anyone Can Build an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem that “a complex system is neither predictable nor quantifiable because its state constantly evolves thanks to the interactions of a large number of agents whose individual behavior impacts the system as a whole”.)

Finally, there is now more interdependence at various levels because more and more things are decentralized, starting with information. (This leads to Martin Gurri’s insight on the unleashing of information as the main contributor to the “revolt of the public”.)

The importance of learning while you build

How can an organization deal with uncertainty? Well, at this point you really need to read Vaughn’s book, which is focused on how chefs in the world of haute cuisine have been adapting their approach to cooking to the context of their industry becoming more uncertain.

But one key insight was elaborated upon in our conversation: if you can’t predict what the future holds (all the possible outcomes and their respective probabilities), then the best approach is to proceed through small, incremental steps and design everything so as to be able to learn from these steps, whether their immediate result be success or failure.

Jeff Bezos approves this message, as illustrated by a famous episode in Amazon’s saga: the launch and eventual failure of the Fire Phone. Here’s what I wrote some time ago in my 11 Notes on Amazon:

Life is very different on the Southern Side as compared to the Northern Side. On the North Face of the Everest, the higher you climb, the more painful it gets. On the Southern Side, however, increasing returns radically change the rules of the game: the higher you climb, the easier it gets (and thus the faster you run up to the peak). Additionally, unlike on the Northern Side, you can slip on the Southern Side without that simple slip meaning death. Here, even failures generate valuable data that can be put to work to improve the customer experience: as Justin Foxreminds us in Harvard Business Review, “an apparent failure like the Amazon Fire phone can be treated as a learning experience rather than a crisis.”

Why innovation is not a goal in itself

Finally, drawing a lesson from his research in the restaurant industry, Vaughn warned founders against being obsessed with innovating all the time, calling it a “false competitive position”.

Sure, focusing on innovation at the expense of everything else gives an early-stage startup the impression that it’s leaving the competition perpetually behind. But ultimately it makes scaling up more difficult because you never learn to do things in an efficient and effective manner, and by innovating constantly you attract only customers who care about innovation.

About the latter observation, definitely have a look at my recent A Few Notes on “Crossing the Chasm”.

Today isn’t the first time Laetitia and I have featured Vaughn’s work. Have a look at (or a listen to) the following:

Laetitia’s essay The Uncertainty Mindset & the Future of Work (Laetitia@Work, September 2020)

My quoting Vaughn’s work (and Laetitia’s essay) in my own essay Three Theses About Cuisine (September 2020)

Another essay by Laetitia on Vaughn’s work: Innovation: What you could learn from the world's famous chefs (October 2020)

Laetitia’s conversation with Vaughn as part of the Building Bridges podcast: Innovating in an Uncertain World | Vaughn Tan (December 2020)

An edited excerpt of their conversation: Lessons of innovation in times of uncertainty (February 2021)

And here are links provided by Vaughn himself:

idk, Vaughn’s game designed “to push you, gently, outside your comfort zone”.

😀 About that current batch at The Family, one of the startups we’re all very fond of is Dark, a venture dedicated to making launching satellites cheaper and more customizable. Read founder Clyde Laheyne’s article that sets the stage for it all: 2030: A Space Odyssey.

🙂 Also in The Family’s world, we directors send a daily newsletter targeted at founders and people interested in startups in general. The latest installment by my colleague Balthazar de Lavergne is an absolute gem, echoing my thoughts on the Diffraction of Venture Capital. Here’s David Galbraith’s praise:

😏 Another installment in the great deeptech controversies. As you remember, I wrote a skeptical column in Sifted, which was then complemented by a rebuke by Zoë Chambers, and a counterpoint by Bill Janeway. Now here’s Martin Kupp with Only startups can move deeptech out of the lab.

😐 You know that I pay a great deal of attention to everything that’s happening in the music industry. Well, there’s been a twist recently: the French conglomerate Vivendi is about to spin out Universal Music Group, which is good news (I think) for the latter; but it will also turn the former into even more of a franco-français thing. Another sign of the Great Fragmentation.

😒 I wrote about the tax-related pitfalls of remote work in this newsletter last year, and in Sifted more recently. Similar problems are currently arising for expats who have had to change their residence because of the pandemic last year. Have a look at Expats stranded by pandemic face heavy tax toll.

😖 It was inevitable: now that the UK has left the EU, business travel between the island and the continent has become a nightmare (and will likely remain so even once the pandemic is over). Michael Skapinker writes as much in the Financial Times: Facing up to the demands of post-Brexit business travel.

If you’ve been forwarded this paid edition of European Straits, you should subscribe so as not to miss the next ones.

From Munich, Germany 🇩🇪

Nicolas

Professor Roger Martin (named the #1 management thinker in the world in 2017) has been writing in Medium a series of essays (currently 20) called the Playing to Win Practitioner Insights (PTW/PI).

They are worth a read. I believe he will bundle them and these will become a book.

His essay #20 is on the difference between Strategy and Planning:

https://link.medium.com/4DGtYa4rWdb

Roger Martin provides another definition of Strategy (and how it is different from Planning).

It is based on his book "Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works" (2013) alongside with A.G. Lafley, former CEO of Procter & Gamble.

What is the Difference? (between Strategy and Planning)

STRATEGY is the act of making an integrated set of choices, which positions the organization to win; while PLANNING is the act of laying out projects with timelines, deliverables, budgets, and responsibilities.

There are 4 important pieces to the definition of business STRATEGY:

First is choices. Strategy specifies the choice to do some things and not others. And that choice obeys the rule that if the opposite is stupid on its face, it doesn’t count as a strategy choice.

Second is integrated set. The choices must fit together and reinforce one another; they aren’t just a list.

Third is positions. The choices explicitly specify a territory in which the organization will play — and will not.

Fourth is to win. Strategy specifies a compelling theory for how the organization will be better than its competitors in the chosen territory.

Your strategy must provide a clear theory of advantage that involves making real choices that are different from those of competitors.

And on any project on which you approve the spending of time and money, you need to make certain that it contributes directly to the realization of that theory of advantage.

His HBR article (Jan-Feb 2014), "The Big Lie of Strategic Planning" is also worth reading:

https://hbr.org/amp/2014/01/the-big-lie-of-strategic-planning