Hi, it’s Nicolas from The Family. Today, I’m covering a topic that I’ve obsessed over for a long time, waiting lines, and explain why it’s important to curb them in the context of COVID-19.

⚠️ The paid version of European Straits launched two weeks ago! In addition to this free edition, my paying subscribers receive a Monday Note as their work week is about to begin and a set of Friday Reads that dig deeper into various topics related to investing in tech startups, especially in Europe.

If you haven’t subscribed, that’s perfectly OK! Still, here’s what you’ve missed lately 😉

My take on the battle between Elliott Management’s Paul Singer and Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey (Paul Singer vs. Twitter), and what it reveals about the future of US tech giants.

A primer on Investing During a Crisis, offering a set of rules to help investors reflect on opportunities and make sure they don’t miss the most promising ones.

An analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis for startups and how to analyze government-led responses, inspired by Ventures Hacks’s Babak Nivi: Quality and Scale, Simultaneously.

If you don’t want to miss the next paid editions, it’s time to subscribe! In the next Friday Reads, I will share a framework to assess the impact of COVID-19 across a portfolio of startup investments.

As for today, I’d like to expand on the idea of “Quality and Scale” and discuss how technology could help us get rid of one of the most dangerous things in these dangerous times: waiting lines 👇

1/ The response to the COVID-19 pandemic seems to involve a familiar pattern. First, the government announces a measure meant to encourage people to increase the distance with others. Then this measure triggers the formation of a crowd in which many, many people are crammed together without the necessary distance to prevent virus transmission.

2/ Here are two examples:

Trump announced a travel ban on people coming from Europe. It immediately prompted US citizens to react, with literally thousands of people gathering in packed airplanes and crowded airports trying to get back to the homeland. Those travelers then were jammed into horrible, virus-ridden waiting lines for health and immigration checks once in the US.

Two days ago, Macron announced a mandatory self-quarantine for everyone in France. Thousands of people in Paris decided they had to leave the city to self-quarantine elsewhere. It immediately clogged transportation systems. All available rental cars were gone within a few hours, leaving people rushing toward full trains where the virus could roam freely.

3/ There’s nothing new here: we had the same problems arise with regards to preventing terrorist attacks. Have you ever wondered why we form long waiting lines to check that people aren’t wearing a bomb, when a terrorist wanting to cause massive casualties could simply plant a bomb (or waive a knife) in the waiting line rather than in the plane?

Just such a tragedy actually happened in Brussels a few years ago. After that, I thought making waiting lines disappear would become a matter of national security. But nothing happened. We still have to wait everywhere, all the time. And curbing those waiting lines is nowhere to be found on the political agenda.

Instead, as we see with the current response to the COVID-19 crisis, we’ve apparently managed to make them even denser and longer!

4/ I think there are two reasons why nobody realizes the urgency of solving the waiting line problem:

In some cases, waiting lines are there by design for marketing purposes. If the line is so long, our reaction is that this restaurant must serve very good food. Or they can exist simply to discourage people from requesting whatever is waiting at the end of the line. There have been arguments made about discouraging immigrants or welfare recipients by making them wait.

The other reason is that it’s related to our paradigm. In the old 20th-century paradigm, most organizations had to choose between quality and scale. A product could be customized and delivered seamlessly, without a waiting line, but it couldn’t scale. Or the product could be available to all, but waiting lines were a necessary price to pay.

5/ I wrote about this in the chapter of my book Hedge about “The Lost Art of State Intervention” (using the UK’s National Health Service as an example!):

The quintessential state bureaucracy is the British National Health Service (NHS), which operates both the single-payer insurance system and most hospitals and medical practices in the UK. The advantage of such a system is fairness: it guarantees everyone access to affordable and professional care no matter their location or income level. The problem is that in today’s context characterized by tax revolt, hatred of government, and fiscal austerity, the quality of the experience provided by the NHS has declined, with longer waiting lines and less customized care. Ultimately it has fallen into a vicious circle in which everybody loses, patients as well as professionals.

For a long time, the problems associated with bureaucracies such as the NHS were tolerated for the sake of operational effectiveness at a large scale. While it was far from perfect, the state was able to act at a larger scale than non-governmental entities. Hence quality could be sacrificed for the benefit of scale and affordability. In healthcare systems, waiting lines and one-size-fits-all were accepted as the only way to access and afford competent doctors and expensive treatments. In postal services, the mother of all public services, the rigidity of the postman’s daily rounds was traded against the service’s availability all the way out into the country’s remotest areas.

6/ People are losing trust in legacy institutions because the current paradigm shift makes them realize something important: the tradeoff between quality and scale doesn’t exist anymore. Now every individual is served on a daily basis by entrepreneurs who use technology to reconcile the problem of providing both quality and scale.

Here’s me in Sifted a few months ago:

The thing with high quality at scale is that we’re all getting used to it. We enjoy the seamlessness of well-designed online applications every day. We find it normal that Amazon can deliver any good to our home within 24 hours. We’re confident in the fact that there will always be a startup that comes up with a cheaper value proposition, forcing all competitors to bring their own prices down while maintaining quality. And this is what generates precious trust and engagement from users in the digital world.

In this context isn’t it normal for protestors wearing yellow vests to ask for lower taxes and better public services simultaneously? If Amazon, Airbnb, Revolut and Dropbox can do it, why not the government? And if the government fails at tackling that challenge isn’t it proof that it is ruled by officials that are incompetent at best, corrupt at worst? Clearly the degrading quality of public services in the context of ever higher taxes on the middle class is one thing, among others, that explains the worldwide phenomenon that former CIA analyst Martin Gurri has dubbed The Revolt of The Public.

7/ How can technology help to curb waiting lines? I won’t expand on telemedicine, which is the obvious example in our current context, or on social services, which have been brilliantly discussed by Hilary Cottam in her book Radical Help.

But let me give other examples in various sectors:

Airlines: Travelling by plane is maddening when it comes to waiting lines. If I’m not mistaken it involves at least 7 of them (as explained here—in French 🇫🇷). And so there has been a lot of thought put into how to cut back on waiting lines in that field. It can be rather low-tech (optimizing the way we board airplanes or streamlining security checks), but I’m sure in the future we’ll witness the rise of startups focused on making plane travel more seamless.

Restaurants: Popular restaurants are prone to generating waiting lines. Technology helps in two ways: it facilitates booking a table in advance, thus skipping the line; and it makes it easier to have your meal delivered rather than eating it at the restaurant. Have a look at those articles (here and here) about making customers pay for a reservation so as to make sure they show up (and leave) on time—thus avoiding waiting lines.

Mobility: Have you ever reflected on how stupid the system of the taxi line at the airport or the train station is? You have one long queue of passengers, and another long queue of taxis, and you pair them one by one—which takes forever. Uber and Lyft have solved that problem: they create an incentive to book slightly in advance and to decide on a location that’s not too crowded. The queue is virtual and thus non-existent for both the driver and the rider.

Retail: When COVID-19 is not roaming around, I live in London, so I can definitely say that this city is a haven for customers in a hurry: you can opt for self-checkout in almost every supermarket, then you can use swift contactless payments (also more hygienic). (By the way, the London Tube has long had fewer waiting lines than the Parisian metro: for years you’ve been able to ride it using contactless payment instead of waiting in line to buy a ticket.)

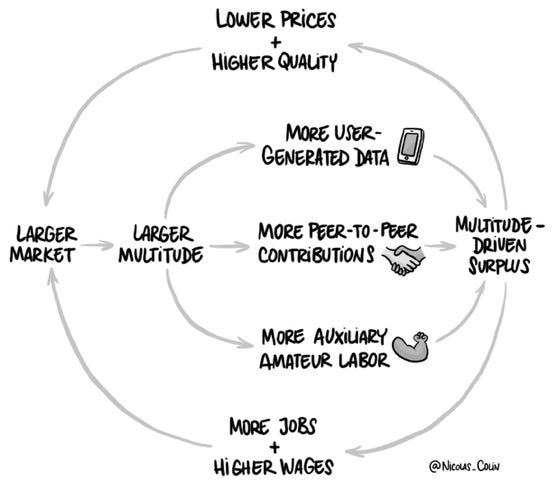

8/ But there’s also a systemic explanation, summed up by the following drawing (also from my book Hedge—illustrated by Marguerite Deneuville). When people are equipped and connected to one another at a large scale, it suddenly becomes easier to do three key things to better match supply and demand and avoid scarcity-induced phenomena such as waiting lines:

You can collect user-generated data and analyze it both at the individual level (to know individuals better and influence their lifestyle in a virtuous way) and at the aggregate level (to assess statistical results and improve the capacity to predict what will happen at scale).

You can orchestrate peer-to-peer interactions to remove the burden from centralized systems. In the context of COVID-19, instead of relying on healthcare professionals, individuals can rely on one another when it comes to prevention or following a treatment protocol.

You can hire part-time workers to provide backup to overwhelmed professionals so that the whole system can absorb peak demand. It’s not about replacing professionals, but rather complementing them with an available, flexible workforce that you train on the job.

9/ It’s easy to understand why Western governments have such a hard time preventing waiting lines. To orchestrate individual interactions so as to avoid people gathering and infecting each other, you need two levers (the stick and the carrot):

You need to spy on them to make sure they don’t sneak around and break the rules (this can be done in a mass-production approach rather than individually).

But you also need to nudge them with individual, contextualized notifications: unlike surveillance and government broadcasts, this requires a direct line of communication.

The balance between those two things will determine the fate of every nation in the weeks and months to come:

Countries such as Mainland China and Singapore manage to use computing and networks both to control people and to individually nudge them towards appropriate behavior in the context of the pandemic. Have a look at this article about the approach in Singapore—and at this one, which is pre-COVID-19 but discusses the now well-known Chinese social credit system.

Western countries, on the other hand, simply don’t have that direct connection with every individual—it’s just not something Western democracies do! And so in the current context they’re forced to rely on mass surveillance (like in Israel) and policing (as will soon be the case across Europe) to prevent people from interacting with one another as the virus spreads.

10/ As we enter the difficult period ahead of us, I’m struck by just how clear things seem in terms of what is needed:

I should have a direct line, via a well-designed application, to at least a doctor, a non-medical government official, and other citizens who find themselves in a similar situation.

Communication should go both ways in a seamless and asynchronous manner (that is, no phone calls).

This communication should include monitoring my condition (and keeping track of my social interactions?) and let me ask the many questions I have.

It should also provide briefings from official sources on how the larger context is evolving, best practices, and where and when to go for an appointment (again, hopefully without a waiting line).

Unfortunately, that application doesn’t exist. We know Western governments are incapable of creating and deploying it (remember the healthcare.gov debacle in the US). And many among us will pay the price in different manners:

People will die from COVID-19 due to the lack of available interlocutors able to answer their questions and examine them when and if they have symptoms.

People will grow annoyed with each other instead of supporting each other. Because as soon as there’s a waiting line, everyone else is either standing in your way or breathing down your neck.

Privacy-invading surveillance and policing will be deployed because that will be the only way to contain the spread of the virus at a large scale.

The lack of convenient support from the government will make everyone wonder why we paid taxes in the first place, and what kind of incompetence/corruption is going on.

Ever longer waiting lines will form whenever we have to interact with anything that’s related to the government, which in turn will mean more people catching the virus, and so on, and so on.

So you see: Waiting lines are a threat to all of us, in terms of convenience, freedom, trust, value creation, and public health, and our governments should do everything in their power to make them disappear.

Let me conclude with this enlightening tweet by Bruno Maçães:

📭 Not much! Our entire team at The Family is working from home, catching up on work and rearranging their lives to cope with the coming weeks of confinement. Obviously we’ve cancelled all events for now, although we won’t slow down on content.

💵 Take a few minutes to read my cofounder Oussama Ammar’s latest piece on his experience as an angel investor: What I learned as a business angel after the last financial crisis.

📕 If you have time to read, have a look at my book Hedge:

Here’s the English version, Hedge: A Greater Safety Net for the Entrepreneurial Age, on Amazon US 🇺🇸 and Amazon UK 🇬🇧.

And the more recently published French version, Un contrat social pour l’âge entrepreneurial.

The comprehensive reading list attached to the European Straits weekly essay has been moved to the Friday Reads paid edition. Subscribe if you want to receive that list on Friday!

From Normandy, France 🇫🇷

Nicolas