Why Debt Capital Is a Good Fit for Europe (and Why Europe Is Lagging Behind Anyway)

European Straits #238

The Agenda 👇

A new iteration on revenue-based financing in Europe

Thumbs up/down for last week

A list of recently unlocked essays from the archive

You’re probably aware of the impressive development of debt capital as a way to fund tech startups these days. There always was a niche segment called ‘venture debt’, but it’s only been in the past two years that debt has become more of a mainstream lever to fund tech startups. I thought I would share a recap of what’s been happening and where we are going, with relevant quotes as well as a reading list.

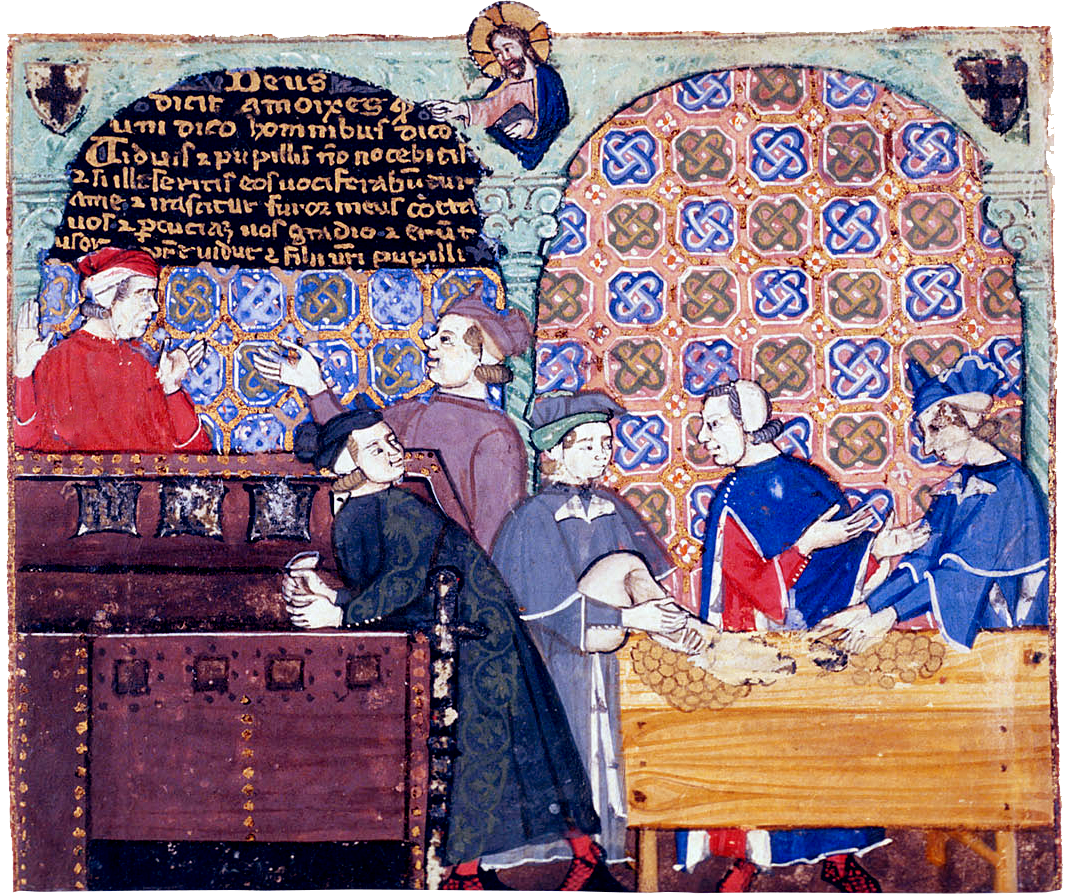

1/ One event that looks like it triggered the whole fury was the publication of an essay titled Debt Is Coming by Alex Danco.

Alex used to work at Social Capital with Chamath Palihapitiya. Now he is with Shopify where he’s working on facilitating access to capital for businesses built on top of Shopify. He had to get interested in debt at some point because debt is the most common way to fund a merchant business, and Shopify is essentially a platform for merchants!

The main point in ‘Debt Is Coming’ is the following:

If you’re a tech founder raising capital today, there’s really one mainstream way to fund it: by selling equity. The VC model capital stack, which the Silicon Valley venture ecosystem has optimized itself around, is the one-size-fits-all funding model for startups of all shapes and sizes. We know it like muscle memory at this point. If your career began after the dot com crash, as mine and I’m sure many of yours did, you’ve probably never known any other way. But the deployment period is a different game. And when FK and PK get really aligned with each other, the best tool in the game isn’t equity anymore.

(Alex himself says he didn’t trigger anything—he just published the right essay at the right time, as many founders and financiers were already working hard to make it happen.)

2/ Now, debt is nothing new in the tech world. For one, as I already mentioned, there has long been something known as ‘venture debt’. But it’s always been kind of a mixed bag: not great for founders, and not great for lenders, either. Here’s what Alex Danco (again) was writing last year (check out the whole thread):

And:

If it isn’t optimal for anybody, no wonder why there wasn’t a positive feedback loop to turn the venture debt sector into a massive segment of capital markets for startups. (And this without even mentioning regulations standing in the way of making venture debt mainstream, as is the case in France.)

An interesting player in that field, however, is Silicon Valley Bank. Here are excerpts from a deep dive published in 2015 in The Wall Street Journal:

Close connections—and lots of them—are an essential part of the business strategy at what in many ways is the hometown bank of America’s tech industry. When startups get their first investor check, it often gets deposited at the Santa Clara, Calif., bank, which also loans money to startups for working capital.

The bank offers invitation-only mortgages to company founders and venture-capital executives and helps venture-capital firms fund their investments. The bank’s parent, SVB Financial Group, owns warrants in 1,625 companies. Warrants give SVB the right to buy shares in those companies…

When borrowers are in financial trouble, SVB often makes a “comfort call” to venture-capital firms that provided funding to the startup. For instance, if the venture-capital firms express willingness to do another funding round, the bank sometimes relaxes loan terms, according to some borrowers.

3/ There’s another way: tech companies that tap into the bond market. One famous precedent is when Amazon borrowed money after having gone public in 1997. The story was told in detail by famed venture capitalists Mary Meeker and Bill Gurley in an episode of the great Vox podcast Land of the Giants. Here’s my take in Investing During a Crisis (March 2020):

The situation was dire, and it could easily be seen by looking at Amazon’s accounts (remember that it went public in 1997, only three years after being founded). When the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, Amazon had never turned a profit, and it had burnt more than $3B in less than 6 years of existence. In short, it was almost wiped out when the music stopped.

[Fortunately,] Bezos wasn’t alone in this fight. Of great help to him was Joy Covey, his then-CFO, who realized before others that if Amazon was a retailer, it could raise capital on the bond market with its future cash flows as collateral. Covey left the company shortly thereafter and then died in a tragic accident in 2013, so few people have heard her name; still, she was instrumental in helping Amazon survive the big crisis that was the year 2000 in the startup world.

4/ Why was Amazon able to issue bonds while most other tech companies were stuck with equity capital? Precisely because Amazon was essentially a merchant at the time, and any merchant is reassuring for a lender: they look at recurring cash flow from customers and are able to discount them to derive the net present value of the business; even if there aren’t tons of customers, there’s still an inventory that has value and that can be used as collateral. Since a merchant business is relatively easy to explain to money lenders, why bother with raising equity capital and getting diluted in the process?

To be fair, Amazon has always looked to be more than a merchant. Its model relies on combining several powerful feedback mechanisms, as I’ve explained in 11 Notes on Amazon. But a cardinal rule of corporate finance is that if part of your business is a merchant business, then your business should be partly financed by debt rather than by equity capital.

5/ This leads me to why Europe seems to be a good fit for tech startups accessing more debt capital. Europe’s main characteristic is that it’s fragmented (see my Will Fragmentation Doom Europe to Another Lost Decade?). As a result, European tech founders are really stuck with two options:

Category #1—Either they focus on their domestic market and renounce reaching a large scale, thus effectively capping the increasing returns to scale they can enjoy over time.

Category #2—Or they look outward and try to build a global business from Day One, most likely in the SaaS sector.

(I admit it’s rare for a European founding team to reason in such terms. More likely, they’ll discover along the way whether their business falls into Category #1 or Category #2—or, to borrow categories introduced by Andreessen Horowitz’s Anish Acharya, “default local” or “default global”.)

6/ But here’s what’s interesting: in both cases (‘default local’ and ‘default global’), these businesses are a rather good fit for raising debt capital.

A default local business will be reassuring for lenders because it usually comes with reliance on tangible assets and/or compliance with demanding regulatory requirements and/or fitting in with specific local customs. In every case, that makes the business easier to defend, therefore even if it’s a tech business cash flows are easier to predict than when competition happens at a larger scale.

Few people realize it, but focusing on a particular geography has its advantages: you trade scalability in exchange for defensibility—and there’s nothing that money lenders love more than a defensible business (whether defensibility can be spotted in assets held on the balance sheet or recurring cash flows on the P&L statement).

As for a default global business, it’s too fragile for debt at the early stages, but once it’s up and running, the very nature of the business (software-as-a-service) makes future revenue easy to model. That is where new techniques for designing revenue-based financial products come into play.

7/ Does that mean that every tech business can now be funded with debt capital rather than equity capital? No. In effect, what I see is a spectrum, with businesses sitting at either extremity lending themselves quite well to debt (pun intended 😉): either you’re a quasi-traditional business and it’s reassuring for traditional lenders, or you’re a pure SaaS business and you fit into the credit scoring models of a new generation of revenue-based lenders.

In both cases, such businesses seem to fit the European context quite well: either a tech startup that’s focused on a local market, or a tech startup that grows a SaaS business at the global level.

What’s missing from this picture is all the intermediate businesses that are neither local nor global: more likely multi-geography with an uneven footprint from one market to another, and quite a lot of tweaking to be done on its product to adapt to the local preferences.

These can be great businesses, too! Think of French healthcare champion Doctolib, which also operates in Germany (where I live). The French and German healthcare systems are so different that there’s not much in common between the two markets except for the Doctolib brand. This makes Doctolib an unlikely candidate for raising debt, but it’s still a promising company!

8/ If Europe is such a good fit for raising debt capital rather than equity capital, why isn’t it happening? This is what we discussed in our panel yesterday as part of a webinar sponsored by Capchase and SaaStock (see details here). Here are some of the reasons:

European founders are less sophisticated than their American counterparts and are thus more tolerant of dilution—whereas repeat founders in the US prefer not to make the same mistakes twice and consider debt capital as a viable option early on.

The European startup community as a whole is less sophisticated, therefore there’s this idea that a tech startup should necessarily be funded with equity capital. In fact, a key step in the entrepreneurial journey is to announce that you’ve raised from a VC firm 🚀🚀 It’s not as sexy to announce that you’ve borrowed from [unknown & unsexy lender] at a 10% interest rate with three cohorts of paying customers used as collateral.

I’m sure there’s a wide range of continental and national regulations that stand in the way of designing revenue-based financial products across Europe.

Finally, the European financial services industry is just not as vibrant and innovative as its American counterpart. In fact, I tend to think that there’s a problem with demand (not enough founders seeking to raise debt), but the more critical problem is on the supply side (not enough financial firms interested in seizing the opportunity that this market represents).

9/ Which leads me to Byrne Hobart’s seminal essay on what makes the US such an innovation powerhouse at the global level. According to Byrne, the US financial system and its unrivalled ability to innovate play a key role in attracting the best founders and then helping them to race ahead of their foreign competitors. Let me quote the essay (which is paywalled):

All this makes US outperformance a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Venture capitalists are eager to fund American companies because they know that those companies can be worth a lot when they IPO, and will have access to enough talent to get to the point where an IPO is possible. Founders want to start companies here in part because this is where they'll be able to get them funded and find employees. So the money is chasing the talent (and money), and the talent is chasing the money (and the rest of the talent).

The whole thing turns out to be a momentum trade: the S&P outperforms because of companies like Google and Facebook, and those companies are part of that index because of prior outperformance.

And so when you hear about policy initiatives to help the pan-European entrepreneurial ecosystem take off, you read a lot about basic research, university spinouts, etc. You don’t read much, on the other hand, about financial innovation.

👉 I think it’s time European policy and business leaders wake up to that reality: there’s a frontier in financial services, too, and Europe is lagging behind as others strive to reach it!

10/ Here’s a reading list for those who want to dig deeper into revenue-based financing:

Capitalists Beat Merchants Everytime (me, European Straits, September 2017)

Startup investors should consider revenue share when equity is a bad fit (Allie Burns, TechCrunch, January 2019)

Revenue-based investing: A new option for founders who care about control (David Teten, TechCrunch, July 2019)

Debt is Coming (Alex Danco, Welcome to Dancoland, February 2020)

When Tailwinds Vanish (John Luttig, luttig’s learnings, April 2020)

Principles for Capital Allocation (me, European Straits, April 2020)

Some thoughts on SaaS ABS (Conor Durkin, May 2020)

It's finally the moment for revenue-based startup financing (Julia Neuman, Sifted, June 2020)

The Diffraction of Venture Capital (me, European Straits, July 2020)

Notes on Revenue-Based Financing (me, European Straits, July 2020)

Europe should lead the way on alternatives to traditional VC (me, Sifted, October 2020)

As Venture Capital Grows in Europe, So Could Founders’ Appetites For Different Financing Tools (Chris Metinko, Crunchbase News, July 2021)

There's another funding route in town - and it could fill a vital gap in the financing ecosystem (Henrik Grim, Finextra, September 2021)

😀 One of the most interesting segments in the Twitter/Substack world is the people (usually scholars) writing about the history of innovation. Indeed, if you know how to use it, history is an incredible guide to understand the current state of things and where the world is heading. I’ve been reading Anton Howes since he started publishing his newsletter Age of Invention, but more recently I discovered Matt Clancy and Davis Kedrosky. Have a look at this incredible thread by the latter:

🙂 You never know enough about crypto! I wrote a primer a while ago (see Bitcoin: Innovation Hiding in Plain Sight), and I recently unlocked access to a collection of links and sources (see All About Crypto). But I still don’t find enough crypto-related conversations that are absolutely free of jargon. I was therefore glad to discover this inspiring podcast conversation between policy wonk Ezra Klein (now with the New York Times) and Katie Haun, a former federal prosecutor who is now a general partner in charge of Andreessen Horowitz’s crypto funds. Give it a listen: Opinion | A Crypto Optimist Meets a Crypto Skeptic.

😏 I mentioned Doctolib above 👆 And I’m glad that the pandemic was used as an opportunity by the French government to try and nurture a national champion in the healthcare sector. Indeed, over the past months, Doctolib has become an indispensable partner to the French authorities for orchestrating and facilitating the nation-wide effort to vaccinate everyone in the country. The Financial Times tells the whole story here: France finds growth prescription with health app Doctolib.

😐 Supply chains have consequences! If they’re encountering gaps and frictions, businesses have to pay more to access key resources or ship their products across the world. This is discussed in this article: Asos boss exits as firm warns profits to plunge—and it echoes what I was writing last year in A Thesis For Sector-Focused Hedge Funds, namely that accelerating growth in a tangible sector also means strains on the underlying logistics and ultimately a reward for the largest players in the industry.

😒 I love Moneyball (actually one of my favorite business-related movies), but as a European I still don’t understand the first thing about baseball. Not only is it difficult to decipher, it also seems to be very boring—at least that’s what we Europeans think, but it appears some Americans agree, if this article is to be believed: MLB Rule Changes: Atlantic League Tests Tweaks Meant to Save Baseball.

An American friend just wrote to me about it, let me quote them: “If there's a difference between watching baseball and waiting to die, I'm not sure what it is.”

😖 One of my recent Sifted columns was about the increased difficulty of immigrating to the UK following Brexit (at least from the EU)—inspired by the sobering personal story told in the Süddeutsche Zeitung by German journalist Michael Neudecker. Having read this recent article, What is a passenger locator form and why is it so frustrating? (in Quartz), it appears that simply travelling to the UK, even for a few days, is painful—in part because of the pandemic and the precautionary measures it requires, but also because of bad design and a backward-looking bureaucratic culture.

📚 I unlocked more essays from the European Straits archive recently. Here’s the list:

🔥 Investing During a Crisis (March 2020)

🔮 A Thesis For Sector-Focused Hedge Funds (September 2020)

🏭 SaaS Is the New Manufacturing (November 2020)

🤓 All About Crypto (February 2021)

And here’s the Twitter thread including all unlocked essays since last June:

Sign up to European Straits if you don’t want to miss the next issues 🤗

From Munich, Germany 🇩🇪

Nicolas

Is it enough money/debt supply for the EU tech companies, who would like to avail for the debt financing scheme?